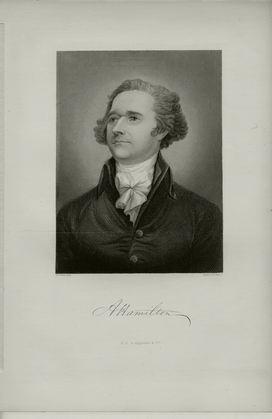

Alexander Hamilton

First Secretary of the Treasury

Click on an image to view full-sized

ALEXANDER HAMILTON

was born a British subject on the island of Nevis in the West Indies on January

11, 1755. His father was James Hamilton, a Scottish merchant of St. Christopher.

Hamilton's mother was Rachael Fawcette Levine, of French Huguenot descent. When

Rachael was very young, she had married a Danish proprietor of St. Croix named

John Michael Levine. Ms. Levine left her husband and was later divorced from him

on June 25, 1759. Under the Danish law which had granted her divorce, she was

forbidden from remarrying. Thus, Hamilton's birth was illegitimate.

Business

failures resulted the bankruptcy of his father and with the death of his mother,

Alexander entered the counting house of Nicholas Cruger and David Beekman,

serving as a clerk and apprentice at the age of twelve. By the age of fifteen,

Alexander was left in charge of the business. Opportunities for regular

schooling were very limited. With the aid of funds advanced by friends, Hamilton

studied at a grammar school in Elizabethtown, New Jersey. In 1774, he graduated

and entered King's College (now Columbia University) in New York City and

obtained a bachelor's of arts degree in just one year.

The War of

Independence had began and at a mass meeting held in the fields in New York City

on July 6, 1774, Hamilton made a sensational speech attacking British policies.

Hamilton's military aspirations flowered with a series of early

accomplishments. On March 14, 1776, he was commissioned captain of a company of

artillery set up by the New York Providential Congress. Hamilton's company

participated at the Battle of Long Island in August of 1776. At White Plains, in

October of 1776, his battery guarded Chatterton's Hill and protected the

withdrawal of William Smallwood's militia. On January 3, 1777, Hamilton's

military reputation won the interest of General Nathaniel Greene. General Greene

introduced the young Captain to General Washington with a recommendation for

advancement. Washington made Hamilton his aide-de-camp and personal secretary

with the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. He served four years as Washington's

personal secretary and confidential aide. Longing for active military service,

he resigned from Washington's staff after a dispute with the general, but

remained in the army. At the Battle of Monmouth (June 28, 1778), Hamilton again

proved his bravery and leadership and he also won laurels at Yorktown (Sept. –

Oct. 1781), where he led the American column in a final assault in the British

works.

Hamilton married

Elizabeth, the daughter of General Philip Schuyler on December 14, 1780. The

Schuylers were one of the most distinguished families in New York. This

connection placed Hamilton in the center of New York society. In 1782, he was

admitted to legal practice in New York and became an assistant to Robert Morris

who was then superintendent of finance.

Hamilton was

elected a member of the Continental Congress in 1782. He at once became a

leading proponent of a stronger national government than what had been provided

for by the Articles of Confederation. As a New York delegate to the

Constitutional Convention of 1787, he advocated a national government that would

have virtually abolished the states and even called for a president for life to

provide energetic leadership. Hamilton left the convention at the end of June,

but he did approve the Constitution subsequently drafted by his colleagues as

preferable to the Articles of Confederation, although it was not as strong as he

wished. Hamilton used his talents to secure the adoption of the Constitution and

published a letter in the Constitution's defense. This letter was published in

the New York Independent Journal on Oct. 2, 1787

Hamilton was one

of three authors of The Federalist. This work remains a classic commentary on

American constitutional law and the principals of government. Its inception and

approximately three-quarters of the work are attributable to Hamilton (the rest

belonging to John Jay and James Madison). Hamilton also won the New York

ratification convention vote for the Constitution against great odds in July

17-July 26, 1788.

During Washington's presidency, Hamilton became the first secretary of the

Treasury. Holding this office from September 11, 1789 to January 31, 1795, he

proved himself a brilliant administrator in organizing the Treasury. In 1790

Hamilton submitted to Congress a report on the public credit that provided for

the funding of national and foreign debts of the United States, as well as for

federal assumption of the states' revolutionary debts. After some controversy,

the proposals were adopted, as were his subsequent reports calling for the

establishment of a national bank. He is chiefly responsible for establishing the

credit of the United States, both at home and abroad. In foreign affairs his

role was almost as influential. He persuaded Washington to adopt a policy of

neutrality after the outbreak of war in Europe in 1793, and in 1794 he wrote the

instructions for the diplomatic mission to London that resulted in the

Anglo-American agreement known as Jay's Treaty. Hamilton also became the

esteemed leader of one of the two great political parties of the time.

After the death

of George Washington, the leadership of the Federalist Party became divided

between John Adams and Hamilton. John Adams had the prestige from his varied and

great career and from his great strength with the people. Conversely, Hamilton

controlled practically all of the leaders of lesser rank and the greater part of

the most distinguished men in the country.

Hamilton, by

himself, was not a leader for the population. After Adams became President,

Hamilton constantly advised the members of the cabinet and endeavored to control

Adams's policy. On the eve of the presidential election of 1800, Hamilton wrote

a bitter personal attack on the president that contained confidential cabinet

information. Although this pamphlet was intended for private circulation, the

document was secured and published by Aaron Burr, Hamilton's political and legal

rival. Based on his opinion of Burr, Hamilton deemed it his patriotic duty to

thwart Burr's ambitions. Burr forced a quarrel and subsequently challenged

Hamilton to a duel. The duel was fought at Weehawken on the New Jersey shore of

the Hudson River opposite New York City. At forty-nine, Hamilton was shot, fell

mortally wounded, and died the following day, July 12, 1804. It is unanimously

reported that Hamilton himself did not intend to fire, his pistol going off

involuntarily as he fell. Hamilton was apparently opposed to dueling following

the fatal shooting of his son Philip in a duel in 1801. Further, Hamilton told

the minister who attended him as he laid dying, "I have no ill-will against Col.

Burr. I met him with a fixed resolution to do him no harm. I forgive all that

happened." His death was very generally deplored as a national calamity.

Apart from his

contributions to The Federalist and his reorganization of the United States

financial system in the 1790's Hamilton is best remembered for his consistent

emphasis on the need for a strong central government. His advocacy of the

doctrine of "implied powers" to advance a broad interpretation of the

Constitution has been invoked frequently to justify the extension of federal

authority and has greatly influence a number of Supreme Court decisions.

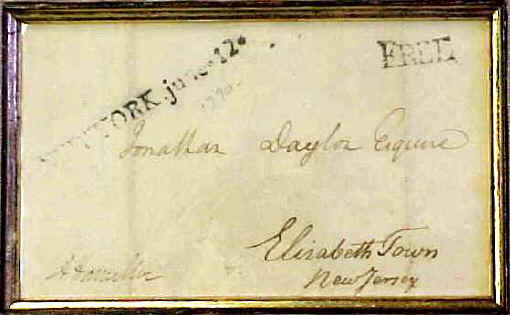

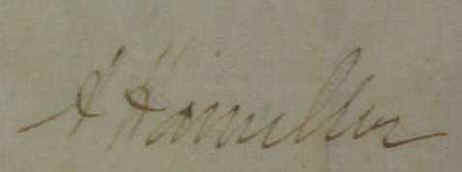

Free franked envelope signed "Alexander Hamilton."

Click

for Larger View

Alexander Hamilton's Military Commission

Courtesy of the National Archives

Edited Appletons Encyclopedia,

Copyright © 2001 VirtualologyTM

HAMILTON, Alexander, statesman, born in the island of Nevis, West Indies, 11

January, 1757; died in New York city, 12 July, 1804. A curious mystery and

uncertainty overhang his birth and parentage, and even the accounts of his son

and biographer vary with and contradict each other. The accepted version is,

that he was the son of James Hamilton, a Scottish merchant, and his wife, a

French lady named Faucette, the divorced wife of a Dane named Lavine. According

to another story, his mother was a Miss Lytton, and her sister came subsequently

to this country, where she was watched over and supported by Hamilton and his

wife. A similar doubt is also connected with his paternity, which now cannot be

solved, even were it desirable. His father became bankrupt "at an early day," to

use Hamilton's own words, and the child was thus thrown upon the care of his

mother's relatives. His education seems to have been brief and desultory, and

chiefly due to the Reverend Hugh Knox, a Presbyterian clergyman of Nevis, who

took a great interest in the boy and kept up an affectionate correspondence with

him in after-days when his former pupil was on the way to greatness.

In 1777 his old tutor wrote to Hamilton that he must be the annalist and

biographer, as well as the aide-de-camp, of General Washington, and the

historiographer of the American war of independence. Before Hamilton was

thirteen years of age it was apparently necessary that he should earn his

living, and he was therefore placed in the office of Nicholas Cruger, a West

Indian merchant. His precocity was extraordinary, owing, perhaps in some

measure, to his early isolation and self-dependence, and at an age when most

boys are thinking of marbles and hockey he was writing to a friend and playmate

of his ambition and his plans for the future. Most boys have day-dreams; but

there is a definiteness and precision about Hamilton's that make them seem more

like the reveries of twenty than of thirteen. Even more remarkable was the

business capacity that he displayed at this time. His business letters, many of

which have been preserved, would have done credit to a trained clerk of any age,

and his employer was apparently in the habit of going away and leaving this mere

child in charge of all the affairs of his counting house. The boy also wrote for

the local press, contributing at one time an account of a severe hurricane that

had devastated the islands, which was so vivid and strong a bit of writing that

it attracted general attention.

This literary success, joined probably to the friendly advocacy of Dr. Knox,

led to the conviction that something ought to be done for a boy who was clearly

fitted for a higher position than a West Indian counting house. Funds were

accordingly provided by undefined relatives and more distinct friends, and thus

equipped, Hamilton sailed for Boston, Massachusetts, where he arrived in

October, 1772, and whence he proceeded to New York. Furnished by Dr. Knox with

good letters, he speedily found friends and counselors, and by their advice went

to a school in Elizabethtown, New Jersey, where he studied with energy to

prepare for college, and employed his pen in much writing, of both prose and

poetry. He entered King's college, New York now Columbia, and there with the aid

of a tutor made remarkable progress. While he was thus engaged, our difficulties

with England were rapidly ripening. Hamilton's natural inclinations were then,

as always, toward the side of order and established government, but a visit to

Boston in the spring of 1774, and a close examination of the questions in

dispute, convinced him of the justice of the cause of the colonies. His

opportunity soon came. A great meeting was held in the fields, 6 July, 1774, to

force the lagging Tory assembly of New York into line. Hamilton was among the

crowd, and as he listened he became more and more impressed, not by what was

said, but by what the speakers omitted to say. Pushing his way to the front, he

mounted the platform, and while the crowd cried "A collegian! A collegian!"

this stripling of seventeen began to pour out an eloquent and fervid speech in

behalf of colonial rights.

Once engaged, Hamilton threw himself into the struggle with all the intense

energy of his nature. He left the platform to take up the pen, and his two

pamphlets--"A Full Vindication" and "The Farmer Refuted"

--attracted immediate and general attention. Indeed, these productions were so

remarkable, at a time when controversial writings of great ability abounded,

that they were generally attributed to Jay and other well-known patriots. The

discovery of their authorship raised Hamilton to the position of a leader in New

York. Events now moved rapidly, the war for which he had sighed in his first

boyish letter came, and he of course was quick to take part in it.

Early in 1776 he was given the command of a company of artillery by the New

York convention, and by his skill in organization, and his talent for command,

he soon had a body of men that furnished a model of appearance and discipline at

a time when those qualities were as uncommon as they were needful. At Long

Island and at White Plains the company distinguished itself, and the gallantry

of the commander, as well as the appearance of the men, which had already

attracted the notice of General Greene, led to

an offer from Washington of a place on his staff. This offer Hamilton accepted,

and thus began the long and intimate connection with Washington which suffered

but one momentary interruption. Hamilton filled an important place on

Washington's staff, and his ready pen made

him almost indispensable to the commander-in-chief. Beside his immediate duties,

the most important task that fell to him was when he was sent to obtain troops

front General Gates, after the

Burgoyne campaign. This was a difficult and

delicate business; but Hamilton conducted it with success, and, by a wise

admixture of firmness and tact, carried his point. He also took such part as was

possible for a staff officer in all the battles fought by Washington, and in the

Andre affair he was brought into close contact both with Andre and Mrs. Arnold,

of whom he has left a most pathetic and picturesque description.

On 16 February, 1781, Hamilton took hasty offence at a reproof given him by

Washington, and resigned from the staff, but he remained in the army, and at

Yorktown commanded a storming party, which took one of the British redoubts.

This dashing exploit practically closed Hamilton's military service in the

Revolution, which had been highly creditable to him both as a staff and field

officer. In the midst of his duties as a soldier, however, Hamilton had found

time for much else. On his mission to Gates he met at Albany Miss Elizabeth

Schuyler, whom he married on 14 December, 1780, and so became connected with a

rich and powerful New York family, which was of marked advantage to him in many

ways. During the Revolution, too, he had found leisure to study finance and

government, and his letters on these topics to

Robert Morris and James Duane display a remarkable grasp of both subjects.

He showed in these letters how to amend the confederation and how to establish a

national bank, and his plans thus set forth were not only practicable, but

evince his peculiar fitness for the great work before him. His letters on the

bank, indeed, so impressed Norris that when Hamilton left the army and was

studying law, Morris offered him the place of continental receiver of taxes for

New York, which he at once accepted. At the same time he was admitted to the

bar, and he threw himself into the work of his profession and of his office with

his wonted zeal.

The exclusion of the Tories from the practice of the law gave a fine opening

to their young rivals on the patriot side; but the business of collecting taxes

was a thankless task, which only served to bring home to Hamilton more than ever

the fatal defects of the confederation. From these uncongenial labors he was

relieved by an election to congress, where he took his seat in November, 1782.

The most important business then before congress was the ratification of peace;

but the radical difficulties of the situation arose from the shattered finances

and from the helplessness and imbecility of the confederation. Hamilton flung

himself into these troubles with the enthusiasm of youth and genius, but all in

vain. The case was hopeless. He extended his reputation for statesmanlike

ability and brilliant eloquence, but effected nothing, and withdrew to the

practice of his profession in 1783, more than ever convinced that the worthless

fabric of the confederation must be swept away, and something better and

stronger put in its place. This great object was never absent from his mind, and

as he rapidly rose at the bar he watched with a keen eye the course of public

affairs, and awaited an opening. Matters went rapidly from bad to worse. The

states were bankrupt, and disintegration threatened them. Internecine commercial

regulations destroyed prosperity, and riot and insurrection menaced society. At

last Virginia, in January, 1786, proposed a convention at Annapolis, Maryland,

to endeavor to make some common commercial regulations.

Hamilton's opportunity had come, and, slender as it was, he seized it with a

firm grasp. He secured the election of delegates from New York, and in company

with Egbert Benson betook himself to Annapolis in September, 1786. After the

fashion of the time, only five states responded to the call; but the meager

gathering at least furnished a stepping-stone to better things. The convention

agreed upon an address, which was drawn by Hamilton, and toned down to suit the

susceptibilities of Edmund Randolph. This

address set forth the evil condition of public affairs, and called a new

convention, with enlarged powers, to meet in Philadelphia, 2 May, 1787. This

done, the next business was to make the coming convention a success, and

Hamilton returned to New York to devote himself to that object. He obtained an

election to the legislature, and there fought the hopeless battles of the

general government against the Clintonian forces,

and made himself felt in all the legislation of the year; but he never lost

sight of his main purpose, the appointment of delegates to Philadelphia. This he

finally accomplished, and was chosen with two leaders of the opposition, Yates

and Lansing, to represent New York in the coming convention. Hamilton's own

position despite his victory in obtaining delegates was trying; for in the

convention the vote of the state, on every question, was east against him by his

colleagues. He, however, did the best that was possible.

At an early day, when a relaxing and feeble tendency appeared in the

convention, he introduced his own scheme of government, and supported it in a

speech of five hours, His plan was much higher in tone, and much stronger, than

any other, since it called for a president and senators for life, and for the

appointment of the governors of states by the national executive. It aimed, in

fact, at the formation of an aristocratic instead of a Democratic republic. Such

a scheme had no chance of adoption, and of course Hamilton was well aware of

this, but it served its purpose by clearing the atmosphere and giving the

convention a more vigorous tone. After delivering his speech, Hamilton withdrew

from the convention, where his colleagues rendered him hopelessly inactive, and

only returned toward the end to take part in the closing debates, and to affix

his name to the constitution.

It was when the labors of the convention were completed and laid before the

people that Hamilton's great work for the constitution really began. He

conceived and started "The Federalist,"

and wrote most of those famous essays which riveted the attention of the

country, furnished the weapons of argument and exposition to those who

"thought continentally" in all the states, and did more than any thing else

toward the adoption of the constitution. In almost all the states the popular

majority was adverse to the constitution, and in the New York ratifying

convention the vote stood at the outset two to one against adoption. In a

brilliant contest, Hamilton, by arguments rarely equaled in the history of

debate, either in form or eloquence, by skilful management, and by wise delay,

finally succeeded in converting enough votes, and carried ratification

triumphantly. It was a great victory, and in the Federal procession in New York

the Federal ship bore the name of "Hamilton." From the convention the

struggle was transferred to the polls. George

Clinton was strong enough to prevent the choice of senators, but at the

election he only retained his own office by a narrow majority; his power was

broken, and the Federalists elected four of the six representatives in congress.

In this fight Hamilton led, and when the choice of senators was finally made he

insisted, in his imperious fashion, on the choice of

Rufus King and General Schuyler, thus

ignoring the Livingstons, a political blunder

that soon cost the Federalists control of the state of New York.

In April, 1789, Washington was inaugurated, and when the treasury department

was at, last organized, in September, he at once placed Hamilton at the head of

it. In the five years that ensued Hamilton did the work that lies at the

foundation of our system of administration, gave life and meaning to the

constitution, and by his policy developed two great political parties. To give

in any detail an account of what he did would be little less than to write the

history of the republic during those eventful years. On 14 January, 1790, he

sent to congress the first "Report on the Public Credit," which is one of

the great state papers of our history, and which marks the beginning and

foundation of our government. In that wonderful document, and with a master's

hand, he reduced our confused finances to order, provided for a funding system

and for taxes to meet it, and displayed a plan for the assumption of the state

debts. The financial policy thus set forth was put into execution, and by it our

credit was redeemed, our union cemented, and our business and commercial

prosperity restored. Yet outside of this great work and within one year Hamilton

was asked to report, and did report fully, on the raising and collection of the

revenue, and on a scheme for revenue cutters; as to estimates of income and

expenditure; as to the temporary regulation of the currency; as to

navigation-laws and the coasting trade; as to the post office; as to the

purchase of West Point; as to the management of the public lands, and upon a

great mass of claims, public and private. Rapidly, effectively, and successfully

were all these varied matters dealt with and settled, and then in the succeeding

years came from the treasury a report on the establishment of a mint, with an

able discussion of Coins and coinage; a report on a national bank, followed by a

great legal argument in the cabinet, which evoked the implied powers of the

constitution; a report on manufactures, which discussed with profound ability

the problems of political economy and formed the basis of the protective policy

of the United States; a plan for an excise; numerous schemes for improved

taxation; and finally a last great report on the public credit, setting forth

the best methods for managing the revenue and for the speedy extinction of the

debt. In the midst of these labors Hamilton was assailed in congress by his

enemies, who were stimulated by Jefferson,

led by James Madison and William B. Giles, and

in an incredibly short time, in a series of reports on loans, he laid bare every

operation of the treasury for three years, and thereafter could not get his

foes, even by renewed invitations, to investigate him further.

Outside of his own department, Hamilton was hardly less active, and in the

difficult and troubled times brought on by the French revolution he took a

leading part in the determination of our foreign policy, he believed in a strict

neutrality, and had no lemming to France. He sustained the neutrality

proclamation in the cabinet, and defended it in the press under the signature of

"Pacificus." He strenuously supported Washington in his course toward

France, and constantly urged more vigorous measures toward Edmond Charles Genet

(q. v.) than the cabinet as a whole would adopt. During this period, too, his

quarrel with Jefferson, which really typified the growth of two great political

parties, came to a head. Jefferson sustained and abetted Freneau in his attacks

upon the administration and the financial policy, and upon the secretary of the

treasury most especially. Hamilton, too, forgetful of the dignity of his office,

took up his pen and in a series of letters to the newspapers lashed Jefferson

until he writhed beneath the blows. At last Washington interfered, and a peace

was patched up between the warring secretaries; but the relation was too

strained to endure, and Jefferson soon resigned and retired to Virginia.

Hamilton was contemplating a similar step, but postponed taking it because he

wished to complete certain financial arrangements, and he also felt unwilling to

leave his office until the troubles arising in Pennsylvania from the excise were

settled. These disturbances culminated in open riot and insurrection; but

Washington and Hamilton were fully prepared to deal with the emergency. A

vigorous proclamation was issued, an overwhelming force, which Hamilton

accompanied, was marched into the insurgent counties, and the so-called

rebellion faded away.

Hamilton now felt free to withdraw from the cabinet, a step that he was

compelled to take from a lack of resources sufficient to support a growing

family, and he accordingly resigned on 31 January, 1795. His neglected practice

at once revived, and he soon stood at the head of the New York bar. But even his

incessant professional duties could not keep him from public affairs. The

Jay negotiation, which he had done much to set on

foot, came to an end, mid the treaty that resulted from it produced a fierce

outburst of popular rage, which threatened to overwhelm Washington himself.

Hamilton defended the treaty with voice and pen, writing a famous series of

essays signed "Camillus," which had a powerful influence in changing public

opinion. He was also consulted constantly by Washington, almost as much as if he

had continued in the cabinet, and he furnished drafts and suggestions for

messages and speeches, besides taking a large share in the preparation of the

"Farewell Address."

Hamilton not only corresponded with and advised the president, but maintained

the same relation with the members of the cabinet, and this fact was one

fruitful source of the dissensions that arose in the Federalist party after the

retirement of Washington. Hamilton supported John Adams

loyally, if not very cordially, at the election of 1796, and intended to give

him an equally loyal support when he assumed office, but the situation was an

impossible one. Adams was the leader of the party de jure, Hamilton de facto,

and at least three members of the cabinet looked from the first beyond their

nominal and official chief to their real chief in New York. If Adams had

possessed political tact, he might have managed Hamilton; but he neither could

nor would attempt it, and Hamilton, on his side, was equally imperious and

equally determined to have his own way. The two leaders agreed as to the special

commission to France, and the commission went. They agreed as to the attitude to

be assumed after the exposure of the "X. Y. Z." correspondence, and all

went well. But, when it came to the provisional army, Adams's jealousy led him

to resist Hamilton's appointment to the command, and a serious breach ensued.

The influence of Washington prevailed, however, and Hamilton was given the

post of inspector-general. For two years he was absorbed in the military duties

thus imposed upon him, and his genius for organization comes out strongly in his

correspondence relating to the formation, distribution, and discipline of the

army. In the mean time the affairs of the party went from bad to worse. Mr.

Adams reopened negotiations with France, which disgusted the war Federalists,

and then expelled Timothy Pickering and James

McHenry from the cabinet, 12 May, 1800. He also gave loud utterance to his

hatred of Hamilton, which speedily reached the latter's ears, and the Federalist

party found themselves face to face with an election and torn by bitter

quarrels. The Federalists were beaten by their opponents under the leadership of

Burr in the New York elections, mid Hamilton,

smarting from defeat, proposed to Jay to call together the old legislature and

refer the choice of electors to the people in districts. The proposition was

wrong and desperate, and wholly unworthy of Hamilton, who seems to have been

beside himself at the prospect of his party's impending ruin and the consequent

triumph of Jefferson. He also made the fatal mistake of openly attacking Adams,

and the famous pamphlet that he wrote against the president, after depicting

Adams as wholly unfit for his high trust, lamely concluded by advising all the

Federalists to vote for him. Such proceedings could have but one result, and the

Federalists were beaten. The victors, however, were left in serious

difficulties, for Burr and Jefferson received an equal number of votes, and the

election was thrown into the house of representatives. The Federalists, eager

for revenge on Jefferson, began to turn to Burr, and now Hamilton, recovered

from his lit, of anger, threw himself into the breach, and, using all his great

influence, was chiefly instrumental in securing the election of Jefferson,

thereby fulfilling the popular will and excluding Burr, a great and high-minded

service, which was a fit close to his public life.

After the election of Jefferson, Hamilton resumed the practice of his

profession, and withdrew more and more into private life. But he could not

separate himself entirely from politics, and continued to write upon them, and

strove to influence and strengthen his party. As time wore on, and the breach

widened between Jefferson and Burr, the latter renewed his intrigues with the

Federalists, but through Hamilton's influence was constantly thwarted, and was

finally beaten for the governorship of New York. Burr then apparently determined

to fix a quarrel upon his life-long enemy, which was no difficult matter, for

Hamilton had used the severest language about Burr--not once, but a hundred

times--and it was easy enough to bring it home to him. Hamilton had no wish to

go out with Burr but he was a fighting man, and, moreover, he was haunted by the

belief that democracy was going to culminate in the horrors of the French

revolution, that a strong man would be needed, and that society would turn to

him for salvation -- a work for which he would be disqualified by the popular

prejudice if he declined to fight a duel. He therefore accepted the challenge,

met Burr on 11 July, 1804, on the bank of the Hudson at Weehawken, and fell

mortally wounded at the first fire.

His tragic fate called forth a universal burst of grief, and drove Burr into

exile, an outcast and a conspirator. The accompanying illustration represents

the tomb that marks his grave in Trinity churchyard, New York. The preceding

one, on page 57, is a picture of "The Grange," Hamilton's country residence on

the upper part of Manhattan island. The thirteen trees that he planted to

symbolize the original states of the Union survive in majestic proportions, and

the mansion is still standing on the bluff overlooking the Hudson on one side

and Long Island sound on the other, not far from 145th Street.

As time has gone on Hamilton's fame has grown, and he stands today as the

most brilliant statesman we have produced. His constructive mind and

far-reaching intellect are visible in every part of our system of government,

which is the best and noblest monument of his genius. His writings abound in

ideas which there and then found their first expression, and which he impressed

upon our institutions until they have become so universally accepted and so very

commonplace that their origin is forgotten. He was a brave and good soldier, and

might well have been a great one had the opportunity ever come. He was the

first, political writer of his time, with an unrivalled power of statement and a

dear, forcible style, which carried conviction in every line. At the time of his

death he was second to no man at the American bar, and was a master in debate

and in oratory. In his family and among his friends he was deeply beloved and

almost blindly followed. His errors and faults came from his strong, passionate

nature, and his masterful will impatient of resistance or control. Yet these

were the very qualities that carried him forward to his triumphs, and enabled

him to perform services to the American people which can never be forgotten.

There are several portraits of the statesman by John Trumbull, and one by

Wiemar; also a marble bust, modelled from life, by Ceraechi in 1794, of which

the accompanying illustration, on page 56, is a copy. A full-length statue of

Hamilton stands in the Central Park of New York.

Hamilton was the principal author of the series of essays called the

"Federalist," written in advocacy of a powerful and influential national

government, which were published in a New York journal under the signature of

"Publius" in 1787-'8, before the adoption of the Federal constitution. There

were eighty-five papers in all, of which Hamilton wrote fifty-one, James Madison

fourteen, John Jay five, and Madison and Hamilton jointly three, while the

authorship of the remaining twelve have been claimed by both Hamilton and

Madison. As secretary of the treasury, he presented to congress an elaborate

report on the public debt in 1789, and one on protective duties on imports in

1791. In the "Gazette of the United States," under the signature "An

American," he assailed Jefferson's financial views, while both were members

of Washington's cabinet (1792); under that of "Pacificus," defended in

print the policy of neutrality between France and England (1793); and in a

series of essays, signed "Camillus," sustained the policy of ratifying

Jay's treaty (1795). Other signatures used by him in his newspaper controversies

were "Cato," "Lucius Crassus," "Phocion," and "Scipio."

In answer to the charges of corruption made by Monroe, he published a

pamphlet, containing his correspondence with Monroe on the subject and the

supposed incriminating letters on which the charges were based (1797). His

"Observations on Certain Documents" (Philadelphia, 1797) was republished in

New York in 1865. In 1798 he defended in the newspapers the policy of increasing

the army. His "Works," comprising the "Federalist," his most

important official reports, and other writings, were published in three volumes

(New York, 1810). His "Official and other Papers," edited by Francis L.

Hawks, appeared in 1842. in 1851 his son, John C., issued a carefully prepared

edition of his "Works," comprising his correspondence and his political

and official writings, civil and military, in seven volumes. A still larger

collection of his "Complete Works," including the "Federalist,"

his private correspondence, and many hitherto unpublished documents, was edited,

with an introduction and notes, by Henry Cabot Lodge (9 vols., 1885). In 1804

appeared a "Collection of Facts and Documents relative to the Death of

Major-General Alexander Hamilton," by William Coleman. The same year his

"Life" was published in Boston by John Williams, under the pen-name

"Anthony Pasquin," a reprint of which has been issued by the Hamilton club

(New York, 1865). A "Life of Alexander Hamilton" (2 vols., 1834-'40) was

published by his son, John Church, who also compiled an elaborate work entitled

"History of the Republic of the United States, as traced in the Writings of

Alexander Hamilton and his Contemporaries," the first volume of which

contains a sketch of his father's career (1850-'8). See also his "Life"

by Henry B. Renwick (1841); "Life and Times of Alexander Hamilton," by

Samuel M. Smucker (Boston, 1856); "Hamilton and his Contemporaries," by

Christopher J. Riethmueller (1864); "Life of Hamilton," by John T. Morse,

Jr. (1876);" Hamilton, a Historical Study," by George Shea (New York,

1877); "Life and Epoch of Alexander Hamilton," by the same author

(Boston, 1879)" and "Life of Hamilton," by Henry Cabot Lodge (American

statesmen series, 1882). A list of the books written by or relating to Hamilton

has been published under the title of "Bibliotheca Hamiltonia" by Paul L. Ford

(New York, 1886). --His wife, Elizabeth, daughter of General Philip Schuyler,

born in Albany, New York, 9 August, 1757; died in Washington, D. C., 9 November,

1854. At the time of their marriage Hamilton was one of General Washington's

aides, with the rank of lieutenant colonel. She rendered assistance to her

husband in his labors, counselled him in his affairs, and kept his papers in

order for him, preserving the large collection of manuscripts, which was

acquired by the United States government in 1849, and has been utilized by the

biographers of Alexander Hamilton and by historians, who have traced by their

light the secret and personal influences that decided many public events between

1775 and 1804. The accompanying portrait of Mrs. Hamilton, painted by James

Earle, represents her at the age of twenty-seven.

--Their son, Philip Hamilton, born 22 January,

1782, was graduated at Columbia in 1800, and died of a wound received in a duel

24 November, 1801, on the same spot where his father fell three years later. The

young man, who showed much promise, became involved in a political quartel, and

was challenged by his antagonist, whose name was Eckert. After the affair the

father regarded with abhorrence the practice of duelling. He recorded his

condemnation in a paper, written before going to the fatal meeting with Burr.

--Another son, Alexander

Hamilton, soldier, born in New York city, 16 May, 1786; died there, 2

August, 1875, was graduated at Columbia in 1804, studied law, and was admitted

to practice. He went abroad, and was with the Duke of Wellington's army in

Portugal in 1811, but returned on hearing rumors of impending war with Great

Britain. He was appointed captain of United States infantry in August, 1813, and

acted as aide-de-camp to General Morgan Lewis in 1814. In 1822 he was appointed

United States district attorney in Florida, and in 1823 one of the three Florida

land-commissioners. His last years were passed in New Brunswick, New Jersey, and

in New York city, where he engaged in real estate speculations.

--Another son, James Alexander Hamilton, lawyer, born in New York city, 14

April, 1788; died in Irvington, New York, 24 September, 1878, was graduated at

Columbia in 1805. He served in the war of 1812-'15 as brigade major and

inspector in the New York state militia, and afterward practiced law. He was

acting secretary of state under President Jackson in 1829, being appointed ad

interim on 4 March, but surrendering the office on the regular appointment of

Martin Van Buren, two days later. On 3 April he was nominated United States

district attorney for the southern district of New York. The degree of LL.D. was

conferred upon him by Hamilton college, he published "Reminiscences of

Hamilton, or Men and Events, at Home and Abroad, during Three Quarters of a

Century" (New York, 1869).--

Another son, John Church Hamilton, lawyer, born in Philadelphia,

Pennsylvania, 22 August, 1792; died in Long Branch, New Jersey, 25 July, 1882,

was graduated at Columbia in 1809. He studied law, and practised in New York

city. He was commissioned a lieutenant in the United States army in March, 1814,

and served as aide-de-camp to General Harrison, bug resigned on 11 June, 1814.

He spent many years in preparing memoirs of his father, and editing the latter's

works (see above).

--Another son, William Steven Hamilton, born in New York city, 4 August,

1797; died in Sacramento, California, 7 August, 1850, entered the United States

military academy in 1814, but left before his graduation. He was appointed

United States surveyor of public lands in Illinois, and served as a colonel of

Illinois volunteers in the Black Hawk war, commanding a reconnoitering party

under General Atkinson in 1832. He held various offices, removed to Wisconsin,

and thence to California.

--The youngest son, Philip Hamilton, jurist, born in New York city, 1 June,

1802; died in Poughkeepsie, New York, 9 July, 1884, married a daughter of Louis

McLane. He was assistant district attorney in New York city, and for some time

judge-advocate of the naval retiring board in Brooklyn.

-Schuyler Hamilton, soldier, son of John Church Hamilton, born in New York

city, 25 July, 1822, was graduated at the United States military academy in

1841, entered the 1st infantry, and was on duty on the plains and as assistant

instructor of tactics at West Point. He served with honor in the Mexican war,

being brevetted for gallantry at Monterey, and again for his brave conduct in an

affair at Nil Flores, where he was attacked by a superior force of Mexican

lancers, and was severely wounded in a desperate hand-to-hand combat. From 1847

till 1854 he served as aide-de-camp to General Winfield Scott. At the beginning

of the civil war he volunteered as a private in the 7th New York regiment, and

was attached to the staff of General Benjamin F. Butler, and then acted as

military secretary to General Scott until the retirement of the latter.

He next served as assistant chief of staff to General Henry W. Halleck, at

St. Louis, Missouri, with the rank of colonel, he was commissioned

brigadier-general of volunteer's on 12 November, 1861, and ordered to command

the department of St. Louis. He participated in the important operations of the

armies of the Tennessee and of the Cumberland, was the first to suggest the

cutting of a canal to turn the enemy's position at Island No. 10, and commanded

a division in the operations against that island and New Madrid, for which he

was made a major-general on 17 September, 1862. At the battle of Farmington he

commanded the reserve. On 27 February, 1863, he was compelled by feeble health

to resign. From 1871 till 1875 he filled the post of hydrographic engineer for

the department of docks in New York city. He is the author of a "History of the

National Flag of the United States" (New York, 1852), and on 14 June, 1877, the

centennial anniversary of its adoption, delivered an address on "Our National

Flag."

--Allan McLane Hamilton, physician, son of Philip, born in Brooklyn,

New York, 6 October, 1848, was graduated at the College of physicians and

surgeons in New York city in 1870, and practiced in that city, devoting his

attention to nervous diseases. He invented a dynamometer in 1874, and was one of

the first to practice galvano-cautery in the United States, and the first to

employ monobromate of camphor in treating delirium tremens and nitro-glycerine

in epilepsy. He had charge in 1872-'3 of the New York state hospital for

diseases of the nervous system, afterward became visiting physician to the

epileptic and paralytic hospital. On Blackwell's island, New York city, and

lectured on nervous diseases in the Long Island college hospital. In the trial

of President Garfield's assassin he testified as an expert in behalf of the

government. He edited in 1875 the "American Psychological Journal," is the

author of a work on" Clinical Electro-Therapeutics" (New York, 1873), and also

of textbooks on "Nervous Diseases" (1878-'81), and "Medical Jurisprudence"

(1887), and has published in professional journals articles on epilepsy, sensory

epilepsy, ascending general paresis, tremors, and incoordination.