Benjamin Harrison

Signer of the Declaration of Independence

HARRISON,

Benjamin, signer of the Declaration of Independence, born in Berkeley,

Charles City County, Virginia, about 1740; died in April, 1791. The general

impression that his family was descended from Harrison the regicide appears to

be erroneous. As a member of the burgesses in 1764 he served on the committee

that prepared the memorials to the king, lords, and commons; but in 1765, with

many other prominent men, opposed the stamp act resolutions of Henry as

impolitic. He was chosen in 1773 one of the committee of correspondence which

united the colonies against Great Britain in 1774, was appointed one of the

delegates to congress, and was four times re-elected to a seat in that body. As

a member of all the Virginia conventions to organize resistance, he acted with

the party lad by Pendleton in favor of " general united

opposition."

On 10 June, 1776, as chairman of

the committee of the whole house of congress, he introduced the resolution that

had been offered three days before by Richard

Henry Lee, declaring the independence of the American colonies, and on 4

July he reported the Declaration of Independence, of which he was one of the

signers. On his return from congress he became a member of the Virginia house of

delegates under the new constitution, was chosen speaker, and filled that office

until 1781, when he was twice elected governor of the commonwealth. As a

delegate to the Virginia convention of 1788, he opposed the ratification of the

Federal constitution, taking the ground of Patrick

Henry, James Monroe, and others, that it was a national and not a Federal

government, though when the instrument was adopted he gave it his hearty

support. At the time of his death he was a member of the Virginia legislature.

In person Benjamin Harrison was large and fleshy; in spite of his suffering from

gout, his good humor was unfailing. Although without conspicuous intellectual

endowments, he was a man of excellent judgment and the highest sense of honor,

with a courage and cheerfulness that never faltered, and a "downright

candor" and sincerity of character which conciliated the affection and

respect of all who knew him

-- more --

BENJAMIN

HARRISON was born in 1726 on

Berkeley, the family plantation beautifully situated on the banks of the James

River overlooking the seaport of Petersburg and Richmond. He

was a descendant of a family long established in Virginia, his father having

married the eldest daughter of the King's surveyor general. Young

Harrison was the eldest son of ten children. He

was a student in the College of William and Mary when, his father and two of his

sisters were all killed in the mansion house, by a lightning strike during a

thunderstorm. Harrison left college

before graduation and returned home to manage his father's estate. Although

he was considered young to be entrusted with such a charge, he displayed unusual

good judgment and prudence in his responsibilities.

Harrison's family had long been distinguished as political leaders and he was

appointed at an early age to sustain the reputation to which he had been born. He

started his political career around 1764 and he continued to hold political

offices throughout his lifetime, being elected to a seat whenever his other

offices permitted. As a member of

the provincial assembly, Harrison soon became outstanding. He

united common good sense with great firmness and the ability to make decisions. Besides

being quite wealthy, and having made respectable connections by marriage, he was

naturally a political leader and he held the confidence of his constituents. The

British, being aware of his influence and respectability, were anxious to have

him, and proposed to name him a member of the executive council of Virginia, a

position few would have had the firmness to decline.

Harrison, although a young man,

was not seduced by the rank conferred by office. In

opposition to the British, he identified himself with the people, whose rights

and liberties he pursued with zeal. As

a member of the House of Burgesses in 1764, he served on the committee that

prepared the memorials to the King, Lords and commons, but in 1765, he opposed

the stamp act resolutions. He was

chosen in 1773 as one of the committee of correspondence that united the

colonies against Britain. In 1774,

he was appointed one of the delegates to the continental congress and was four

times re-elected to that seat.

Harrison was witty, jovial and

entertaining, having a wry, often black sense of humor that delighted his fellow

congressmen. When there was

discussion about the possibility of being hanged for signing the Declaration of

Independence, the heavyweight Harrison was reported to have uttered to Elbridge

Gerry, a very thin man, "I shall have all the advantage over you. It

will be all over in a minute for me, but you will be kicking in the air half an

hour after I am gone." Harrison

loved his family and his several large plantations and was an intimate friend of

George Washington. He married

Elizabeth Bassett and they had seven children who survived infancy. Of his

children, his third son, William Henry Harrison, would become the ninth

President of the United States. His

great grandson, Benjamin Harrison, would become our twenty-third President.

During nearly every session of

congress, Harrison represented his state of Virginia, distinguishing himself in

many important positions. He was

chairman of the board of war and held that office until he left congress in

1777. He was also often called to

preside as chairman of the committee of the whole house, in which post he was

extremely popular. He occupied that

chair during the deliberations on the dispatches of General Washington, the

settlement of commercial restrictions against Britain, the state of the

colonies, the regulation of trade and during the momentous question on the

debates for the declaration of independence.

Towards

the end of 1777, Harrison resigned his seat in congress and returned to

Virginia. He was once again elected

to his state legislature. In 1782,

he was elected to the office of chief magistrate of Virginia and became one of

the state's most popular governors. He

was twice re-elected governor and in 1785, having become ineligible by the

provisions of his state's constitution, he returned to private life, carrying

with him the esteem of his fellow citizens.

In

1788, when the new constitution of the United States was submitted to Virginia,

he was elected a member of the state convention. Owing

to his advanced years, and to increasing attacks of gout, he did not take a very

active part in the debates of the convention. He

was generally in favor of the constitution, provided certain amendments could be

made to it, but voted against its unconditional ratification.

In the spring of 1791, Harrison was again severely attacked by gout, and he

partially recovered. In the month of

April, he was again elected a member of his state legislature. On

the evening of the day after his election, following a festive party in

celebration of his election, he was again stricken with gout and died at

Berkeley on April 24, 1791.

Source: Centennial

Book of Signers

For

a High-resolution version of the original

Declaration

For a High-resolution version of the Stone

engraving

We invite you to read a transcription

of the complete text of the Declaration as presented by the National Archives.

&

The article "The

Declaration of Independence: A History,"

which provides a detailed account of the Declaration, from its drafting through

its preservation today at the National Archives.

Virtualology

welcomes

the addition of web pages with historical documents and/or scholarly papers on

this subject. To submit a web link

to this page CLICK

HERE. Please be sure to

include the above name, your name, address, and any information you deem

appropriate with your submission.

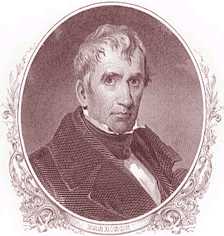

William Henry Harrison

9th President of The United States

William Henry Harrison, ninth

president of the United States, born in Berkeley, Charles City County, Virginia,

9 February, 1773; died in Washington, D. C., 4 April, 1841, was educated at

Hampden Sidney college, Virginia, and began the study of medicine, but before he

had finished it accounts of the Indian outrages that had been committed on the

western frontier raised in him a desire to enter the army for its defense.

Robert Norris, who had been appointed his guardian on the death of his father in

1791, endeavored to dissuade him, but his purpose was approved by Washington,

who had been his father's friend, and he was commissioned ensign in the 1st

infantry on 16 August, 1791. He joined his regiment at Fort Washington, Ohio,

was appointed lieutenant of the 1st sub-legion, to rank from June, 1792, and

afterward joined the new army under General Anthony Wayne. He was made

aide-de-camp to the commanding officer, took part, in December, 1793, in the

expedition that erected Fort Recovery on the battlefield where St.

Clair had been defeated two years before, and, with others, was thanked by

name in general orders for his services.

He participated in the engagements with the Indians that began on 30 June,

1794, and on 19 August, at a council of war, submitted a plan of march, which

was adopted and led to the victory on the Miami on the following day. Lieutenant

Harrison was specially complimented by General Wayne, in his dispatch to the

secretary of war, for gallantry in this fight, and in May, 1797, was made

captain, and given command of Fort Washington. Here he was entrusted with the

duty of receiving and forwarding troops, arms, and provisions to the forts in

the northwest that had been evacuated by the British in obedience to the Jay

treaty of 1794, and was also instructed to report to the commanding general on

all movements in the south, and to prevent the passage of French agents with

military stores intended for an invasion of Louisiana. While in command of this

fort he formed an attachment for Anna, daughter of John Cleves Symmes. Her

father refused his consent to the match, but the young couple were married in

his house during his temporary absence, and Symmes soon became reconciled to his

son-in-law. Peace having been made with the Indians, Captain Harrison resigned

his commission on 1 June, 1798, and was immediately appointed by President John

Adams secretary of the northwest territory, under General Arthur St. Clair

as governor, but in October, 1799, resigned to take his seat as territorial

delegate in congress.

In his one year of service, though he was opposed by speculators, he

secured the subdivision of the public lands into small tracts, and the passage

of other measures for the welfare of the settlers. During the session, part of

the northwest territory was formed into the territory of Indiana, including the

present states of Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin, and Harrison was

made its governor and superintendent of Indian affairs. Resigning his seat in

congress, he entered on the duties of his office, which included the

confirmation of land grants, the defining of townships, and others that were

equally important. Governor Harrison was reappointed successively by President

Jefferson and President Madison. He organized the legislature at Vincennes

in 1805, and applied himself especially to improving the condition of the

Indians, trying to prevent the sale of intoxicating liquors among them, and to

introduce inoculation for the small-pox. He frequently held councils with them,

and, although his life was sometimes endangered, succeeded by his calmness and

courage in averting many outbreaks. On 30 September, 1809, he concluded a treaty

with several tribes by which they sold to the United States about 3,000,000

acres of land on Wabash and White rivers. This, and the former treaties of

cession that had been made, were condemned by Tecumseh (q. v.) and other chiefs

on the ground that the consent of all the tribes was necessary to a legal sale.

The discontent was increased by the action of speculators in ejecting Indians

from the lands, by agents of the British government, and by the preaching of

Tecumseh's brother, the "prophet" (see ELLSKWATAWA), and it was

evident that an outbreak was at hand.

The governor pursued a conciliatory course, gave to needy Indians

provisions from the public stores, and in July, 1810, invited Tecumseh and his

brother, the prophet, to a council at Vincennes, requesting them to bring with

them not more than thirty men. In response, the chief, accompanied by 400 fully

armed warriors, arrived at Vincennes on 12 August The council, which was held

under the trees in front of the governor's house, was nearly terminated by

bloodshed on the first day, but Harrison, who foresaw the importance of

conciliating Tecumseh, prevented, by his coolness, a conflict that almost had

been precipitated by the latter. The discussion was resumed on the next day, but

with no result, the Indians insisting on the return of all the lands that had

recently been acquired by treaty. On the day after the council Harrison visited

Tecumseh at his camp, accompanied only by an interpreter, but without success.

In the following spring depredations by the savages were frequent, and the

governor sent word to Tecumseh that, unless they should cease, the Indians would

be punished. The chief promised another interview, and appeared at Vincennes on

27 July, 1811, with 300 followers, but, awed probably by the presence of 750

militia, professed to be friendly. Soon afterward, Harrison, convinced of the

chief's insincerity, but not approving the plan of the government to seize him

as a hostage, proposed, instead, the establishment of a military post near

Tippecanoe, a town that had been established by the prophet on the upper Wabash.

The news that the government had given assent to this scheme was received

with joy, and volunteers flocked to Vincennes. Harrison marched from that town

on 26 September, with about 900 men, including 350 regular infantry, completed

Fort Harrison, near the site of Terre Haute, Indiana, on 28 October, and,

leaving a garrison there, pressed forward toward Tippecanoe. On 6 November, when

the army had reached a point a mile and a half distant from the town, it was met

by messengers demanding a parley. A council was proposed for the next day, and

Harrison at once went into camp. taking, however, every precaution against a

surprise. At four o'clock on the following morning a fierce attack was made on

the camp by the savages, and the fighting continued till daylight, when the

Indians were driven from the field by a cavalry charge. During the battle, in

which the American loss was 108 killed and wounded, the governor directed the

movements of the troops, he was highly complimented by President Madison in his

message of 18 Dec., 1811, and was also thanked by the legislatures of Kentucky

and Indiana.

On 18 June, 1812, war was declared between Great Britain and the United

States. On 25 August, Governor Harrison, although not a citizen of Kentucky, was

commissioned major-general of the militia of that state, and given command of a

detachment that was sent to re-enforce General Hull, the news of whose surrender

had not yet reached Kentucky. On 2 September, while on the march, he received a

brigadier-general's commission in the regular army, but withheld his acceptance

till he could learn whether or not he was to be subordinate to General James

Winchester, who had been appointed to the command of the northwestern army.

After relieving Fort Wayne, which had been invested by the Indians, he turned

over his force to General Winchester, and was returning to his home in Indiana

when he met an express with a letter from the secretary of war, appointing him

to the chief command in the northwest. "You will exercise,"

said the letter, "your own discretion, and act in all cases according to

your own judgment."

No latitude as great as this had been given to any commander since Washington.

Harrison now prepared to concentrate his force on the rapids of the Maumee, and

thence to move on Malden and Detroit. Various difficulties, however, prevented

him from carrying out his design immediately. Forts were erected and supplies

forwarded, but, with the exception of a few minor engagements with Indians, the

remainder of the year was occupied merely in preparation for the coming

campaign. Winchester had been ordered by Harrison to advance to the Rapids, but

the order was countermanded on receipt of information that Tecumseh, with a

large force, was at the head-waters of the Wabash. Through a misunderstanding,

however, Winchester continued, and on 18 January captured Frenchtown (now

Monroe, Michigan), but three days later met with a bloody repulse on the river

Raisin from Colonel Henry Proctor. Harrison hastened to his aid, but was too

late. After establishing a fortified camp, which he named Fort Meigs, after the

governor of Ohio, the commander visited Cincinnati to obtain supplies, and while

there urged the construction of a fleet on Lake Erie.

On 2 March, 1813, he was given a major-general's commission. Shortly

afterward, having heard that the British were preparing to attack Fort Meigs, he

hastened thither, arriving on 12 April. On 28 April it was ascertained that the

enemy under Proctor was advancing in force, and on 1 May siege was laid to the

fort. While a heavy fire was kept up on both sides for five days,

re-enforcements under General Green Clay were hurried forward and came to the

relief of the Americans in two bodies, one on each side of Maumee river. Those

on the opposite side from the fort put the enemy to flight, but, disregarding

Harrison's signals, allowed themselves to be drawn into the woods, and were

finally dispersed or captured. The other detachment fought their way to the

fort, and at the same time the garrison made a sortie and spiked the enemy's

guns. Three days later Proctor raised the siege. He renewed his attack in July

with 5,000 men, but after a few days again withdrew.

On 10 September Commander Perry gained his victory on Lake Erie, and on 16

September Harrison embarked his artillery and supplies for a descent on Canada.

The troops followed between the 20th and 24th, and on the 27th the army landed

on the enemy's territory. Proctor burned the fort and navy yard at Malden and

retreated, and Harrison followed on the next day. Proctor was overtaken on 5

October, and took position with his left flanked by the Thames, and a swamp

covering his right, which was still further protected by Tecumseh and his

Indians. He had made the mistake of forming his men in open order, which was the

plan that was adopted in Indian fighting, and Harrison, taking advantage of the

error, ordered Colonel Richard M. Johnson to lead a cavalry charge, which broke

through the British lines, and virtually ended the battle. Within five minutes

almost the entire British force was captured, and Proctor escaped only by

abandoning his carriage and taking to the woods. Another band of cavalry charged

the Indians, who lost their leader, Tecumseh, in the beginning of the fight, and

afterward made no great resistance. This battle, which, if mere numbers alone be

considered, was insignificant, was most important in its results. Together with

Perry's victory it gave the United States possession of the chain of lakes above

Erie, and put an end to the war in uppermost Canada. Harrison's praises were

sung in the president's message, in congress, and in the legislatures of the

different states.

Celebrations in honor of his victory were held in the principal cities of

the Union, and he was one of the heroes of the hour. He now sent his troops to

Niagara, and proceeded to Washington, where he was ordered by the president to

Cincinnati to devise means of protection for the Indiana border. General John

Armstrong, who was at this time secretary of war, in planning the campaign of

1814 assigned Harrison to the 8th military district, including only western

states, where he could see no active service, and on 25 April issued an order to

Major Holmes, one of Harrison's subordinates, without consulting the latter.

Harrison thereupon tendered his resignation, which, President Madison being

absent, was accepted by Armstrong. This terminated Harrison's military career.

In 1814, and again in 1815 he was appointed on commissions that concluded

satisfactory Indian treaties, and in 1816 he was chosen to congress to fill a

vacancy, serving till 1819. While he was in congress he was charged by a

dissatisfied contractor with misuse of the public money while in command of the

northwestern army, but was completely exonerated by an investigating committee

of the house. At this time his opponents succeeded, by a vote of 13 to 11 in the

senate, in striking his name from a resolution that had already passed the

house, directing gold medals to be struck in honor of Governor Shelby, of

Kentucky, and himself, for the victory of the Thames. The resolution was passed

unanimously two years later, on 24 March, 1818, and Harrison received the medal.

Among the charges that were made against him was that he would not have pursued

Proctor at all, after the latter's abandonment of Malden, had it not been for

Governor Shelby; but the latter denied this in a letter that was read before the

senate, and gave General Harrison the highest praise for his promptitude and

vigilance.

While in congress, Harrison drew up and advocated a general militia bill,

which was not successful, and also proposed a measure for the relief of

soldiers, which was passed. In 1819 General Harrison was chosen to the senate of

Ohio, and in 1822 was a candidate for congress, but was defeated on account of

his vote against the admission of Missouri to the Union with the restriction

that slavery was to be prohibited there. In 1824 he was a presidential elector,

voting for Henry Clay, and in the same year he was sent to the United States

senate, where he succeeded Andrew Jackson as

chairman of the committee on military affairs, introduced a bill to prevent

desertions, and exerted himself to obtain pensions for old soldiers. He resigned

in 1828, having been appointed by President John Quincy

Adams United States minister to the United States of Colombia. While there

he wrote a letter to General Simon Bolivar urging him not to accept dictatorial

powers. He was recalled at the outset of Jackson's administration, as is

asserted by some, at the demand of General Bolivar, and retired to his farm at

North Bend, near Cincinnati, Ohio, where he lived quietly, filling the offices

of clerk of the county court and president of the county agricultural society.

In 1835 General Harrison was nominated for the presidency by meetings in

Pennsylvania, New York, Ohio, and other states; but the opposition to Van

Buren was not united on him, and he received only 73 electoral votes to the

former's 170. Four years later the National Whig convention, which was called at

Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, for 4 December, 1839, to decide between the claims of

several rival candidates, nominated him for the same office, with John

Tyler, of Virginia, for vice president. The Democrats renominated President

Van Buren. The canvass that followed has been often called the "log

cabin and hard cider campaign."

The eastern end of General Harrison's house at North Bend consisted of a

log cabin that had been built by one of the first settlers of Ohio, but which

had long since been covered with clapboards. The republican simplicity of his

home was extolled by his admirers, and a political biography of that time says

that "his table, instead of being covered with exciting wines, is well

supplied with the best cider." Log cabins and hard cider, then, became

the party emblems, and both were features of all the political demonstrations of

the canvass, which witnessed the introduction of the enormous mass-meetings and

processions that have since been common just before presidential elections. The

result of the contest was the choice of Harrison, who received 234 electoral

votes to Van Buren's 60.

He was inaugurated at Washington on 4 March, 1841, and immediately

sent to the senate his nominations for cabinet officers, which were confirmed.

They were Daniel Webster, of Massachusetts,

secretary of state; Thomas Ewing, of Ohio, secretary of the treasury; John Bell,

of Tennessee, secretary of war; George E. Badger, of North Carolina, secretary

of the navy; Francis Granger, of New York, postmaster-general; and John J.

Crittenden, of Kentucky, attorney-general. The senate adjourned on 15 March, and

two days afterward the president called congress together in extra session to

consider financial measures. On 27 March, after several days of indisposition,

he was prostrated by a chill, which was followed by bilious pneumonia, and on

Sunday morning, 4 April, he died.

The end came so suddenly that his wife, who had remained at North Bend on

account of illness, was unable to be present at his death-bed. The event was a

shock to the country, the more so that a chief magistrate had never before died

in office, and especially to the Whig party, who had formed high hopes of his

administration. His body was interred in the congressional cemetery at

Washington; but a few years later, at the request of his family, it was removed

to North Bend, where it was placed in a tomb, overlooking the Ohio river. This

was subsequently allowed to fall into neglect, but afterward General Harrison's

son, John Scott, deeded it and the surrounding land to the state of Ohio, on

condition that it should be kept in repair. In 1887 the legislature of the state

voted to raise money by taxation for the purpose of erecting a monument to

General Harrison's memory.

He was the author of a "Discourse on the Aborigines of the Valley

of the Ohio" (Cincinnati, 1838). His life has been written by Noses

Dawson (Cincinnati, 1834); by James Hall (Philadelphia, 1836); by Richard

Hildreth (1839); by Samuel J. Burr (New York, 1840)" by Isaac R. Jackson;

and by H. Montgomery (New York, 1853).

--His wife, Anna, born near Norristown, New Jersey, 25 July, 1775; died

near North Bend, Ohio, 25 February, 1864, was a daughter of John Cleves Symmes,

and married General Harrison 22 November, 1795. After her husband's death she

lived at North Bend till 1855, when she went to the house of her son, John Scott

Harrison, a few miles distant. Her funeral sermon was preached by Horace

Bushnell, and her body lies by the side of her husband at North Bend.

--Their son, John Scott, born in Vincennes, Indiana, 4 October, 1804; died

near North Bend, Ohio, 26 May, 1878, received a liberal education, and was

elected to congress as a Whig, serving from 5 December, 1853, till 3 March,

1857.--A daughter, Lucy, born in Richmond, Virginia; died in Cincinnati, Ohio, 7

April, 1826, became the wife of David K. Este, of the latter city, and was noted

for her piety and benevolence.

--Benjamin, son of John Scott, senator, born in North Bend, Ohio, 20

August, 1833, was graduated at Miami university, Ohio, in 1852, studied law in

Cincinnati, and in 1854 removed to Indianapolis, Indiana, where he has since

resided. He was elected reporter of the state supreme court in 1860, and in 1862

entered the army as a 2d lieutenant of Indiana volunteers. After a short service

he organized a company of the 70th Indiana regiment, was commissioned colonel on

the completion of the regiment, and served through the war, receiving the brevet

of brigadier-general of volunteers on 23 January 1865. He then returned to

Indianapolis, and resumed his office of supreme court reporter, to which he had

been re-elected during his absence in 1864. In 1876 he was the Republican

candidate for governor of Indiana, but was defeated by a small plurality.

President Hayes appointed him on the Mississippi river commission in 1878, and

in 1880 he was elected United States senator, taking his seat on 4 March, 1881.

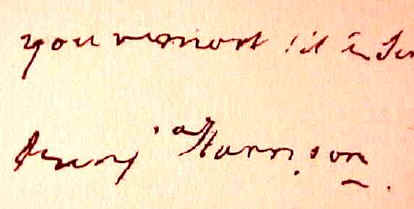

Courtesy of: National

Archives and Records Administration

President William Henry Harrison message nominating

his cabinet, including Daniel Webster as Secretary of State, Thomas Ewing as

Secretary of the Treasury, John Bell as Secretary of War, George E. Badger as

Secretary of the Navy, John J. Crittenden as Attorney General, and Francis

Granger as Post Master General. Page

1 and Page 2.

Presidential

Libraries

Rutherford

B. Hayes Presidential Center

McKinley

Memorial Library

Herbert

Hoover Presidential Library and Museum - has research collections containing

papers of Herbert Hoover and other 20th century leaders.

Franklin

D. Roosevelt Library and Museum - Repository of the records of President

Franklin Roosevelt and his wife Eleanor Roosevelt, managed by the National

Archives and Records Administration.

Harry

S. Truman Library & Museum

Dwight

D. Eisenhower Presidential Library - preserves and makes available for

research the papers, audiovisual materials, and memorabilia of Dwight and Mamie

D. Eisenhower

John

Fitzgerald Kennedy Library

Lyndon

B. Johnson Library and Museum

Richard

Nixon Library and Birthplace Foundation

Gerald

R. Ford Library and Museum

Jimmy

Carter Library

Ronald Reagan Presidential Library

- 40th President: 1981-1989.

George

Bush Presidential Library