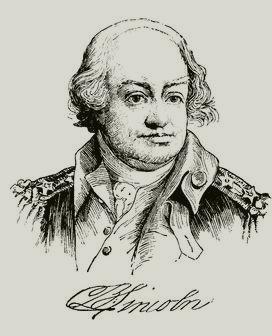

LINCOLN, Benjamin - A Klos Family Project - Revolutionary War General

Click on an image to view full-sized

LINCOLN, Benjamin, soldier, born

in Hingham, Massachusetts, 24 January, 1733; died there, 9 May, 1810. His

father, Benjamin, was born in Hingham in 1700, his family having been among the

first settlers, the name of Thomas Lincoln, a cooper, appearing on the

town-records as early as 1636. He received only a common school education, and

was a farmer until 1773, holding the offices of magistrate, representative in

the provincial legislature, and colonel of militia. He was also a member of the

provincial congresses of Massachusetts, of which he was secretary, and served on

its committee of correspondence. He was active in organizing and training the

Continental troops, and was appointed major-general of state militia in 1776,

and on 23 May, 1776, was placed at the head of a committee to prepare

instructions for the representatives of the town in the general court, previous

to the Declaration of Independence.

The following is an extract from his instructions entered on the records of the

town:

"You are instructed and directed at all times to give your vote and

interest in support of the present struggle with Great Britain. We ask nothing

of her but peace, liberty, and safety. You will never recede from that claim,

and, agreeably to a resolve of the late house of representatives, in case the

honorable Continental congress declare themselves independent of Great

Britain, solemnly engage, in behalf of your constituents, that they will, with

their lives and fortunes, support them in the measure."

In June of that year he commanded the expedition that cleared Boston harbor

of British vessels. After the American defeat on Long Island he was dispatched

by the council of Massachusetts to re-enforce Washington

with a body of militia, and he subsequently participated in the battle of White

Plains and other engagements. At the close of 1776 Lincoln, with the greater

part of 6,000 militia, was engaged with General William Heath in the attack on

Fort Independence, which resulted disastrously. In the beginning of 1777 he

joined Washington at Morristown with a new

levy of militia, and on 19 February was promoted to major-general, having been

recommended by Washington in a letter to congress dated 20 December, 1776:

"In speaking of General Lincoln, I should not do him justice were I

not to add that he is a gentleman well worthy of notice in the military line.

He commanded the militia from Massachusetts last summer, or fall rather, and

much to my satisfaction, having proved himself, on all occasions, an active,

spirited, sensible man. I do not know whether it is his wish to remain in the

military line, or whether, if he should, anything under thee rank he now holds

in the state he comes from would satisfy him."

He was then stationed at Bound Brook, New Jersey, the advanced post of the

British, where he was surprised by a party of 2,000 men under Lord

Cornwallis and General James Grant on 13 April, but escaped with his aides

before he was surrounded. He remained attached to Washington's

command till July, when he was sent with General Benedict

Arnold to act under General Schuyler

against Burgoyne, for which purpose he raised a

body of New England militia. He sent out a successful expedition, which seized

the posts of the enemy at Lake George, and broke Burgoyne's

line of communication. General Lincoln then joined General

Gates at Stillwater, and took command of the right wing. During the battle

of Bemis's Heights he commanded inside the American works, and on the next day,

in leading a small force to a post in the rear of Burgoyne's

army, fell in with a party of British, supposing them to be Americans, and

received a severe wound, which forced him to retire for a year and lamed him for

life.

He rejoined the army in August, 1778, on 25 September was appointed by

congress to the chief command of the southern department, and for several months

he was engaged in protecting Charleston against General Augustine Prevost. Upon

the arrival of Count d'Estaing he co-operated with the French troops and fleet

in the unsuccessful assault on Savannah; but from the unwillingness of his

allies to continue the siege he was forced to return to Charleston, where in the

spring of 1780 he was besieged by a superior British force under Sir

Henry Clinton. After an obstinate defense he was obliged in May to

capitulate, and in November retired to Massachusetts on parole.

In the spring of 1778 he was exchanged, and immediately joined Washington

on Hudson river. He participated in the siege of

Yorktown, and Washington appointed him

to receive the sword of Lord Cornwallis on the

surrender of the British forces. He held the office of secretary of war from

1781 till 1784, after which he retired to his farm, receiving the thanks of

congress for his services.

In 1787 he commanded the forces that quelled Shays's rebellion in western

Massachusetts, and in that year was elected lieutenant-governor of the state.

Upon the establishment of the Federal government he received from Washington

the appointment of collector of the port of Boston, from which office he retired

about two years before his death. He was a member of the commission that made a

treaty with the Creek Indians in 1789, and of the one that in 1793

unsuccessfully attempted to enter into negotiations with the Indians north of

the Ohio, the other members including Thomas Pickering and Beverly Randolph, of

Virginia, the place appointed for the conference being Sandusky. He kept a

journal of this expedition, which was published entire in the collections of the

Massachusetts historical society (series iii., vol. v.). Accompanying this is an

engraving of an outline sketch taken by a British officer present at the meeting

of the Indians on Buffalo creek, representing Randolph, Pickering, and Lincoln,

General Chapin, several Quakers, two British officers, the Indian orator, and

the interpreter. He was also a member of the Massachusetts convention that

ratified the United States constitution and president of the Massachusetts

society of the Cincinnati from its organization until his death.

He was much esteemed by General Washington,

who presented him with a set of epaulettes and sword knots, which he had

received from a French officer. He devoted his last years to literary and

scientific pursuits, and was a member of the American academy of arts and

sciences, and of the Massachusetts historical society. Harvard gave him the

degree of M.A. in 1780. His correspondence during the adoption of the Federal

constitution was large and important, including letters from the leading

patriots, and a letter from Dr. David Ramsey, the historian, dated Charleston,

19 January, 1788, gives an interesting view of the relations then existing

between New England and South Carolina. While secretary of war he wrote long

letters to his son, which he intended to be read at the meetings of the academy,

containing the results of his observations of the physical features of the

south. A paper upon his belief that trees receive nourishment from the

atmosphere instead of the earth, and one on the ravages of worms in trees, were

published in Cary's "American Museum." Many of his writings

appeared about 1790, including a paper on the migration of fishes, in an

appendix to vol. iii. of Dr. Belknap's "History of New Hampshire," and

three essays, published in the collections of the Massachusetts historical

society: "Observations on the Climate, Soil, and Value of the Eastern

Counties in the District of Maine"; "On the Religious State of

the Eastern Counties"; and on the "Indian Tribes, the Causes of

their Decrease, their Claims, etc." His portrait was painted by Henry

Sargent, a copy of which was presented to the Massachusetts historical society.

(See his life by Francis Bowen in Sparks's "American Biography,"'

second series, Boston, 1847.)

Edited Appletons Encyclopedia, Copyright © 2001 VirtualologyTM