New Page 1

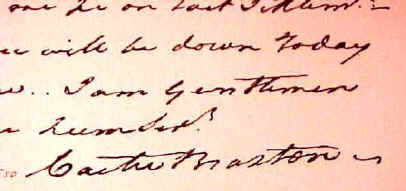

Carter Braxton

Signer of the Declaration of Independence

CARTER

BRAXTON was born on his father's

successful tobacco plantation in Newington, Virginia on September 10, 1736. He

was educated at William and Mary College and, while still in his teens,

inherited the large family estate upon the death of his father. At the age of

nineteen he married a wealthy heiress named Judith Robinson, who died two years

later, leaving two daughters.

After the death

of his wife, Braxton spent three years in England and upon his return home, he

in 1761 he married Elizabeth Corbin, the daughter of a British colonel who was

the Receiver of Customs in Virginia for the King. He lived in great splendor in

richly furnished mansions on two of his plantations and he produced a total of

sixteen children, though only ten of these survived infancy.

Braxton entered

the House of Burgess about that time and in 1765 he supported Patrick Henry's

Stamp Act Resolutions with vigor as the imposition of import taxes were

adversely affecting his own business interests. Braxton was elected in 1774 to

the convention that met in Williamsburg after Lord Dunmore's dissolution of the

assembly, and it was in that body he recommended a general congress of the

colonies. The convention agreed to make a common cause with Boston and to break

off commercial association with Britain.

The Virginia

convention upon reassembling in March 1775, adopted measures for the defense of

the country, and for the encouragement of domestic production of textiles, iron

and gunpowder. On April 20, 1775 Lord Dunmore had taken powder belonging to

Virginia to a British vessel in the James River. Patrick Henry, a leader of the

militia, flew to arms and refused to disband his troops and insisted upon making

reprisals on the King's property in an amount sufficient to cover the value of

the powder. Braxton interceded and obtained from his father-in-law, the receiver

general of customs, a bill on Philadelphia for the amount of Patrick Henry's

demand. Henry dismissed his men and bloodshed was for the time averted.

However, Braxton

did not share the same zeal for freedom from England as did his colleagues. He

was convinced that a possible civil war was far more dangerous than

democracy. Braxton was chosen on December 15, 1775 to succeed Peyton Randolph as

delegate to the Continental congress when Randolph died in October 1775, and

took his seat in February 1776. Eloquently, he took to the floor of Congress to

air his opposition to a hasty and complete break from England. No record exists

on how Braxton actually voted. However, he signed the document on August 2,

1776. Nine days later he returned to Virginia where he took his former seat in

the state legislature. He served there in various capacities until his death.

The great

fortune that Braxton inherited he risked in extensive commercial

enterprises. During the Revolutionary War, just about every shipping vessel in

which he held an interest was either sunk or captured by the British. He fell

deeper and deeper in debt and was forced to sell off his vast land holdings and

the debts due him became worthless on account of the depreciation of the

currency.

Carter Braxton

died of a stroke on October 10, 1797 at the age of sixty-one.

BRAXTON, Carter, signer of the Declaration of Independence, born in

Newington, King and Queen county, Virginia, 10 September, 1736; died in

Richmond, Virginia, 10 October, 1797. He inherited a large estate in land and

slaves from his father and grandfather, was educated at William and Mary

College, and married, at the age of nineteen, a wealthy heiress named Judith

Robinson, who died two years later, leaving two daughters. After spending two or

three years in England he married Elizabeth Corbin, daughter of the king's

receiver-general of customs, and lived in great splendor in richly furnished

mansions on two of his plantations.

He entered the House of Burgesses about 1761, and in 1765 supported Patrick

Henry's stamp-act resolutions with vigor. He was a member of the subsequent

legislatures that were dissolved by the governor, and of the Virginia convention

of 1769. In the assembly elected ill place of the one dissolved by Lord

Botetourt in 1769, Mr. Braxton was appointed on three of the six standing

committees. After its dissolution by Lord Dunmore, 12 October, 1771, he

sufficient to cover the value of the powder, Mr. Braxton interceded and obtained

from his father-in-law, the receiver-general, a bill on Philadelphia for the

amount of Henry's demand, whereupon the latter dismissed his men, and bloodshed

was for the time averted. Braxton was chosen a member of the last House of

Burgesses, which was elected immediately after the dissolution in May, 1774, and

convened on 1 June, 1775. He was a member of the general convention that, after

the flight of the governor on 7 June, was convened in Richmond on 17 July, 1775,

and, assuming the powers of the executive and the legislature, passed acts for

the organization of the militia and minute-men. He was one of the eleven members

of the committee of safety appointed by that body.

Peyton Randolph, delegate to the continental

congress from Virginia, and the first president of that body, died in October,

1775, and when the convention reassembled, on 1 December, in Richmond, and

afterward in Williamsburg, Mr. Braxton was chosen, on 15 December, 1775, to

succeed the deceased representative. He affixed his name to the Declaration of

Independence on 4 July, 1776, but, in consequence of a resolve passed by the

Virginia convention on 20 June, 1776, reducing the number of delegates from

Virginia in the general congress from seven to five, he ceased, on 11 August,

1776, to be a member of the congress. His "Address to the Convention of Virginia

on the Subject of Government" (Philadelphia, 1776) contained sentiments not

relished by the more eager patriots. His popularity was, however, not so much

impaired but that he was elected to succeed William Aylett (who resigned to join

the army) in the general convention, and in virtue of that election he became a

member of the first House of Delegates under the constitution. He was chairman

of the committee of religion, made the reports of the committee of grievances

and propositions, and was a member of the committee of trade, and of important

special committees. He was a member of the House of Delegates in 1777, 1779,

1780, 1781, 1783, and 1785.

In the latter year he supported Jefferson's act for the freedom of religion.

In January, 1786, he was appointed a member of the Privy Council, or council of

state, and remained in that office till 30 March, 1791. He then returned to the

legislature as member for Henrico County, having removed to Richmond in 1786. In

1793 he was again appointed by the general assembly a member of the executive

council, and continued to serve until his death. The great fortune that he

inherited he risked in extensive commercial enterprises, and during the

revolutionary war his vessels were captured by the enemy, the debts due him

became worthless on account of the depreciation of the currency, and he was

involved in endless litigation and interminable pecuniary embarrassments, into

which his sons-in-law and other friends were also drawn.