Edward Braddock -- Major General -- French and Indian War -- Braddock's

Defeat -- A Stan Klos Company

Edward Braddock

British Major General

Photos of the Edward Braddock Landmark and Fort

Necessity outside plaque by: Christopher,

Fort Couch Middle School,

Upper St. Clair, Pennsylvania.

General Edward Braddock's

original burial site

General Edward Braddock's

death scene

While on an expedition in 1755 to capture Fort Duquesne,

General Braddock and his 2400 British regulars were surprised by a force of 900

French and Native Americans at the Monongahela River. Most of his troops

panicked and over 1200 men were killed or seriously wounded. Braddock, himself,

was mortally shot through the arm and into his chest. He died during the British

retreat to Virginia. General Braddock was buried in the middle of the road near

Fort Necessity to avoid his body's detection by the Indians.

Click Here for the

Actual 1755 London Account Of Braddock's Defeat Courtesy of Estoric.com

BRADDOCK, Edward, British soldier,

born in Perthshire, Scotland, about 1695; died near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, 13

July, 1755. He had attained the grade of major general after more than forty

years' service in the British guards, when on the eve of the French war he was

sent here as generalissimo of all the British forces in the colonies. He landed,

20 February, 1755, at Hampton, Virginia, and debarked his troops at Alexandria,

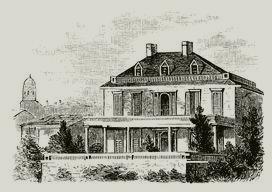

to which point the Virginia levies had also been directed. The house that was

his headquarters in Alexandria, shown in the engraving, is still standing.

The general was a good tactician, but a very martinet, proud, prejudiced, and

conceited. Horace Walpole describes him as "a very Iroquois in disposition,"

and tells an anecdote that sheds light on his character.

"He once had a duel with Col. Glumley, who had been his great friend. As

they were going to engage, Glumley, who had good humor and wit (Braddock had

the latter), said: ' Braddock, you are a poor dog! here, take my purse; if you

kill me, you will be forced to run away, and then you will not have a shilling

to support you.' Braddock refused the purse, insisted on the duel, was

disarmed, and would not even ask for his life."

When Braddock heard that not more than twenty-five wagons could be procured

for the use of the army, he declared that the expedition should not start.

Washington was made his aide-de-camp. At Frederick-town, Benjamin Franklin, then

postmaster-general, with his usual sagacity and energy, undertook to provide the

necessary conveyances, and records the conversation with Braddock in which he

unfolded his intentions.

"After taking Fort Duquesne," said the general, "I am to proceed

to Niagara; and, having taken that, to Frontenac if the season will allow

time, and I suppose it will, for Duquesne can hardly detain me above three or

four days; and then I can see nothing that can obstruct my march to Niagara."

Franklin thought the plan excellent, provided he could take his fine troops

safely to Fort Duquesne, but apprehended danger from the ambuscades of the

Indians, who might destroy his army in detail. The intimation struck Braddock as

absurd, and he said: "These savages may indeed be a formidable enemy to raw

American military, but upon the king's regular and disciplined troops, sir, it

is impossible they should make an impression."

Similar warnings by Washington met with similar replies. The expedition made

slow progress, but at last drew near the fort, and crossed the Monongahela in

regular order ; the drums were beating, the fifes playing, the colors flying,

and their bayonets glittered in the sun. Suddenly, as the van was ascending a

slope with underbrush and ravines on both sides, it was exposed to a murderous

fire from an invisible foe. Braddock ordered the main body to halt, the firing

continued, and the British for the first time heard the terrible war-whoop. The

effect of the Indian rifles, directed by the French, was deadly; most of the

grenadiers and many of the pioneers were shot down, and those who escaped the

bullets were compelled to fall back. The British were ordered to form in line,

but the men were so frightened by the demoniac yells of the hidden savages that

they refused to follow their officers in small divisions.

The Virginians, familiar with Indian warfare, separated, and from behind

sheltering rocks or trees picked off the enemy. Washington suggested to the

general to pursue the same course with the regulars; but he scorned the

advice, and is reported to have said that a British general might dispense with

the military instruction of a Virginia colonel. He insisted that his men should

be formed in regular platoons; they fired by platoons at random at the rocks,

into the ravines and the bushes, and killed a number of Americans -- as many as

fifty by one volley -- while they themselves fell with alarming rapidity.

The officers behaved splendidly, and Braddock's personal bravery was

conspicuous; five horses had been killed under him, when at last a bullet passed

through his right arm and lodged in his lungs. He fell from his horse, and was

with difficulty removed from the ground. The defeat was total, and the rout

complete.

Washington's escape was almost miraculous; sixty-four out of eighty-five

officers were killed or wounded. There is little doubt that, but for the

obstinacy and self-sufficiency of Braddock, the disaster might have been

averted; for the crushing and sanguinary defeat of 9 July was inflicted by a

handful of men, who intended only to molest his advance.

Washington covered the retreat, and the remnant of the army went into camp at

the Great Meadows four days later. Braddock said nothing, but exclaimed in the

evening after the engagement, "Who would have thought it?" Then he

relapsed into silence, unbroken until a few minutes before his death at the

Great Meadows on the evening of 13 July, when he said: "We shall better know

how to deal with them another time."

He was buried before break of day, Washington reading the burial service, for

the chaplain had been wounded. His grave (though now well known, and pointed out

seven miles east of Uniontown) was at the time leveled with the ground to

prevent Indian outrage. See "The History of an Expedition against Fort

Duquesne in 1755, under Major-General Edward Braddock. Edited from the Original

Manuscripts by Winthrop Sargent, 31. A." (Philadelphia, 1855).

Click on an image to view full-sized