George Augustus Howe - A Klos Family Project

Click on an image to view full-sized

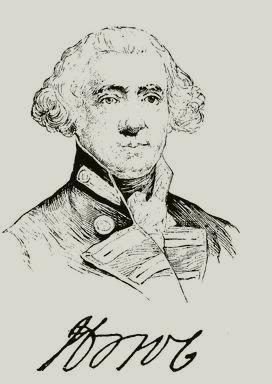

George Augustus Howe

HOWE, George Augustus,

viscount, British soldier, born in England in 1724; died near Fort Ticonderoga,

New York, 5 July, 1758. His father, Emanuel Scrope, was second Viscount Howe of

the Irish peerage. The son entered the army at an early age, soon rose to

distinction, and in 1757 was sent to this country in command of the 60th

regiment, arriving in Halifax, Nova Scotia, in July of this year. He was

transferred to the command of the 55th infantry in September, promoted

brigadier-general in December, and on 6 July, 1758, under Commander-in-Chief

James Abercrombie, landed at the outlet of Lake George. Coming suddenly upon the

French force two days afterward at Fort Ticonderoga, he fell at the head of his

corps in the ensuing skirmish. Howe was idolized by his men, and exercised much

influence with his officers, whom he induced by his example to dress and fare

like the common soldiers, and to abandon the luxurious habits that were then in

vogue. A contemporaneous historian says in allusion to his death, "With

him the soul of the army seemed to expire." The general court of

Massachusetts appropriated £250 for his monument, which was erected in

Westminster Abbey.

His brother, Richard Howe, British naval officer, born in England in 1725;

died there, 5 August. 1799, entered the navy at fourteen years of age, and

served with distinction against the French from 1745 till 1759. On the death of

his brother George in 1758, he succeeded to the family title and estates. At the

conclusion of peace between France and England, he served on the admiralty

board, was appointed treasurer of the navy in 1765, entered parliament for

Dartmouth, and in 1770 was made rear-admiral of the blue, and commanded a fleet

in the Mediterranean. In 1776, with the rank of rear-admiral, he sailed for

North America as joint commissioner with his brother William for restoring peace

with the colonies.

Howe was sincere in his attempts to reconcile the countries, and, as

unsuspicious as he was brave, thought that by riding a, bout the country and

conversing with the principal inhabitants, he could, by moderation and

concession, restore the king's authority. When, after negotiations with Franklin,

he discovered the true attitude of the colonists, he declared that he had been

deceived in accepting a commission that left him no power but to assist in the

subjugation of the colonies by arms. In a second attempt to bring about a

reconciliation, after the retreat from Long Island, he used John Sullivan as a

go-between to congress, but was forced by the American commissioners that had

been appointed to treat with him to acknowledge that his commission, in respect

to acts of parliament, was confined to powers of consultation with private

individuals.

Howe was then variously employed against the American forces for two years,

and in August, 1778, had an indecisive encounter with a superior French fleet

under Count d' Estaing, off the coast of Rhode Island, in which both fleets were

severely shattered by a storm, Howe then resigned his command to Admiral Byron

and returned to England.

In 1782 he was made a peer of Great Britain under the title of Viscount Howe.

In the latter part of this year he succeeded in bringing into the harbor at

Gibraltar the fleet sent to the relief of General Elliot; and for these and

previous services was created Earl and Baron Howe of Langar. In 1793 he was put

in command of the channel fleet, in the next year he gained a victory over the

French on the western coast of France off Ushant, and received the thanks of the

English parliament.

In 1795 he was made admiral of the fleet, and in 1797 a knight of the garter.

His last important service was the suppression of a mutiny in the fleet at

Spithead in 1797. Lord Howe's swarthy complexion gave him, among the sailors,

the sobriquet of "Black Dick." Horace Walpole describes him in

parliament, as "silent as a rock except when naval matters were

discussed, when he spoke briefly but to the point." A severe criticism

of his conduct during the American war was written probably by Lord George

Germaine (London, 1779), and he replied to it in a "Narrative of the

Transactions of the Fleet" (1780). His "Life," with

letters and notes from his journal, was published and edited by Sir John Barrow

(London, 1838)

--Another brother, William Howe, soldier, born in England, 10 August, 1729;

died in Plymouth, England, 12 July, 1814, commanded the light infantry under Wolfe

at the heights of Abraham, near Quebec, in 1759, and in 1775 succeeded General

Thomas Gage as commander-in-chief of the British forces in America. He

commanded at the battle of Bunker Hill,

after the evacuation of Boston retired to Halifax, and in August, 1776, defeated

the colonial forces on Long Island. He took possession of New York on 15

September, defeated Washington at White

Plains, and captured Fort Washington with its garrison of 2,000 men.

In July, 1777, he sailed to Chesapeake bay, defeated Washington

at Brandywine, 11 September, and on the

26th of this month entered Philadelphia. He repulsed the attack of Washington at

Germantown on 4 October, but, instead of breaking up the American camp at Valley

Forge, spent the winter of 1777-'8 in Philadelphia with his army, in indolence

and pleasure. In May, 1778, he was recalled and superseded by Sir Henry Clinton.

His officers, with whom he was personally popular, were indignant at what they

termed the injustice of his removal, and gave him on his departure a grand

entertainment called the "mischianza."

On the investigation of his military conduct by parliament in 1779, he was

acquitted of blame by Lord Grey, Lord Cornwallis. and other military men. who

affirmed that he had done what he could considering the insufficiency of his

force. General Howe became lieutenant of ordnance in 1782, colonel of the 19th

dragoons, and full general in 1786, was governor of Berwick in 1795, and in

1799, on the death of his brother Richard, succeeded to the Irish viscounty. At

the time of his death he was a privy councilor, and governor of Plymouth.

Although brave and an adept in military science, Howe was incapable of

conducting the operations of a great army, and owed his advancement to his name,

and his relationship, by illegitimate descent, to George

III. He is described by General Henry Lee as being "the most

indolent of mortals, who never took pains to examine the merits or demerits of a

cause in which he was engaged." General Howe published a narrative

relative to his command in North America (London, 1780).