New Page 1

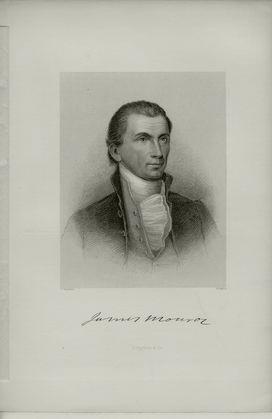

James Monroe

15th President of the United

States

5th under the US Constitution

JAMES MONROE was born on April 28, 1758

in Westmoreland County, Virginia. He was one of five children of Spence Monroe

and Elizabeth Jones who were both natives of Virginia. The Monroe’s lived on a

small farm and young James walked several miles each day to attend the school of

Parson Campbell, who taught him the stern moral code that he followed throughout

his life.

When he was 16, Monroe entered the College of William and Mary. During his

first year there, his father died and the cost of his education and his

guardianship was taken over by his uncle, Judge Joseph Jones, who became his

trusted advisor. The year was 1774 and the colonies were moving ever closer to

war with Great Britain. Young Monroe was finding it difficult to concentrate on

his studies and in 1775, he left college to go to war. He became a lieutenant

and during the Battle of Trenton, his captain was wounded and the command was

given to him. However, he too was wounded at that battle and while recovering he

was named aide-de-camp to Major General Lord Stirling. He fought with George

Washington at Valley Forge and in 1779, and now a major, Monroe was commissioned

to lead a militia of Virginia regiment as a lieutenant colonel. However, his

unit was never formed and his military career was at its end. He became an aide

to Thomas Jefferson, who was the Governor of Virginia at this time. He also

became Jefferson’s student in the study of law and with Jefferson’s

guidance, he began to see what course his life would take.

In 1782, at the age of 24, Monroe was elected to the Virginia State

Legislature. He was the youngest member of the Executive Council and in 1783,

was elected to the United States Congress that was meeting in New York City. He

served in Congress for three years and during this time he became interested in

the settlement of the “western” lands between the Allegheny Mountains and

the Mississippi River. He was chairman of two important expansion committees –

one dealing with travel on the Mississippi River and the other involving the

government of the western lands.

Congress was meeting at that time in New York City, and while there Monroe

met Elizabeth Kortright, whom he married on February 16, 1786. The couple had

three children: Eliza Kortright Monroe (1786-1835), James Spence Monroe

(1799-1800), and Maria Hester Monroe (1803-1850).

In October, 1786, Monroe resigned from Congress and settled in

Fredericksburg, Virginia with his new bride. He was elected to the town council

and once again to the Virginia Legislature. He was a delegate to the Virginia

convention to ratify the new Constitution and was strongly opposed, feeling that

it was a threat to fee navigation of the Mississippi. He voted against the

constitution, but once it was ratified he accepted the new government without

any misgivings.

In 1789, the Monroe’s moved to Albemarle County, Virginia. Their estate,

Ash Lawn, was very near Jefferson’s estate, Monticello. In 1790, he was

elected to a recently vacated seat in the United States Senate and was named to

a full six-year term the following year. In the spring of 1794, Monroe accepted

the diplomatic position of Minister Plenipotentiary to France. His assignment

was to help maintain friendly relations with France despite efforts to remain on

peaceful terms with France’s enemy, Great Britain. Monroe was recalled in

September 1796 and felt he had been betrayed by his opponents who used him to

appease France while they made great concessions to Britain in Jay’s Treaty

that the United States had signed in 1794. He remained bitter about it for the

rest of his life.

Monroe returned home in June 1797 and after two years of retirement from

public office, he was elected governor of Virginia, a position that he served

from 1799 until 1803. His great friend and mentor, Thomas Jefferson had been

elected President in 1800 and in 1803, Monroe was sent back to France to help

Robert R. Livingston complete the negotiations for the acquisition of New

Orleans and West Florida. The French Emperor, Napoleon I, offered to sell

instead the entire Louisiana colony and although the Americans were not

authorized to make such a large purchase, they began negotiations. In April

1803, the Louisiana Purchase was concluded, more than doubling the size of the

nation. Monroe spent the next two years in useless negotiations with Britain and

Spain and returned to the United States in late 1807.

Monroe returned to Virginia politics and once more served in the legislature

and was elected Governor for a second time. In 1811, Monroe became President

Madison’s Secretary of State and when the War of 1812 was declared, he loyally

supported Madison. He served as Secretary of State throughout the war and

simultaneously served as Secretary of War for the latter part. He was back in

uniform at the time of the British attack on Washington and led the Maryland

militia in an unsuccessful attempt to hold off the British at Bladensburg. On

December 24, 1814, the Treaty of Ghent was signed ending the war. In 1815,

Monroe returned to the normal peacetime duties of Secretary of State.

Monroe was the logical presidential nominee at the end of Madison’s second

term, and he won the election easily. On March 4, 1817 James Monroe took his

oath of office. Some of the notable events of his term were: Congress fixed 13

as the number of stripes on the flag to honor the original colonies; the

boundary between Canada and the United States was fixed at the 49th parallel.;

Spain ceded Florida to the United States in exchange for the cancellation of $5

million in Spanish debt; The Missouri Compromise, admitted Missouri as a slave

state, but forbade slavery in any states carved from the Louisiana Territory

north of 36 degrees 30 minutes latitude. By the end of his first term,

Monroe’s administration had been one of high idealism and integrity and his

personal popularity was at an all time high. Monroe was virtually unopposed for

reelection. He carried every state and received every electoral vote cast with

the exception of one, cast by a New Hampshire elector for John Quincy Adams.

With the exception of the Monroe Doctrine, Monroe’s second term as

president was relatively uneventful. The two principles of the Doctrine,

noncolonization and nonintervention, were not new or original. However, it was

Monroe who explicitly proclaimed them as policy and it was a keystone of foreign

policy for many years.

Monroe had no thought of seeking a third term as the election of 1824 neared.

He was 67 years old when he turned over the presidency to John Quincy Adams. He

retired to Oak Hill, Virginia. He was plagued by financial worries and he was

forced to sell his estate Ash Lawn to meet his debts. After his wife died, he

sold Oak Hill and moved to New York City to live with his youngest daughter,

Maria Hester Gouverneur and her husband. Monroe died there on July 4, 1831, the

fifty-fifth anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence.

Following images Courtesy of: National

Archives and Records Administration

Message of President James Monroe at the commencement of the first

session of the 18th Congress The Monroe Doctrine

Unrestricted. (NWL-46-PRESMESS-18AE1-1)

Message of

President James Monroe nominating John Quincy Adams to be Secretary of

State, William Crawford to be Secretary of the Treasury, and Isaac Shelby to be

Secretary of War. (NWL-46-MCCOOK-1(15))

Click on an image to view full-sized

1876 Appleton's Biography on James Monroe.

MONROE, James, fifth president

of the United States, died in Westmoreland county, Virginia, 28 April,

1758" died in New York city, 4 July, 1831. Although the attempts to trace

his pedigree have not been successful, it appears certain that the Monroe family

came to Virginia as early as 1650, and that they were of Scottish origin. James

Monroe's father was Spence Monroe, and his mother was Eliza, sister of Judge

Joseph Jones, twice a delegate from Virginia to the Continental congress. The

boyhood of the future president was passed in his native county, a neighborhood

famous for early manifestations of patriotic fervor. His earliest recollections

must have been associated with public remonstrance against the stamp-act (in

1766), and with the reception (in 1769)of a portrait of Lord Chatham, which was

sent to the gentlemen of Westmoreland, from London, by one of their

correspondents, Edmund Jennings, of Lincoln's Inn.

To the college of William and Mary, then rich and prosperous, James Monroe

was sent but soon after his student life began it was interrupted by the

Revolutionary war. Three members of the faculty and twenty-five or thirty

students, Monroe among them, entered the military service. He joined the army in

1776 at the headquarters of Washington in

New York, as a lieutenant in the 31 Virginia regiment under Colonel Hugh Mercer.

He was with the troops at Harlem, at White Plains, and at Trenton,

where, in leading the advance guard, he was wounded in the shoulder.

During 1777-'8 he served as a volunteer aide, with the rank of major, on the

staff of the Earl of Stifling, and took part in the battles of the Brandywine,

Germantown, and Monmouth.

After these services he was commended by Washington for a commission in the

state troops of Virginia, but without success, he formed the acquaintance of Governor

Jefferson, and was sent by him as a military commissioner to collect

information in regard to the condition and prospects of the southern army. He

thus attained the rank of lieutenant-colonel but his services in the field were

completely interrupted, to his disappointment trod chagrin. His uncle, Judge

Jones, at all times a trusted and intimate counselor, then wrote to him; "

You do well to cultivate the friendship of Mr. Jefferson . . . and while you

continue to deserve his esteem, he will not withdraw his countenance."

The future proved the sagacity of this advice, for Monroe's intimacy with

Jefferson, which was then established, continued through life, and was the key

to his early advancement, and perhaps his ultimate success. The civil life of

Monroe began on his election in 1782 to a seat in the assembly of Virginia, and

his appointment as a member of the executive counsel. He was next a delegate to

the 4th, 5th, and 6th congresses of the confederation, where, notwithstanding

his youth, he was active and influential. Bancroft says of him that when

Jefferson embarked for France, Monroe remained "not the ablest but the

most conspicuous representative of Virginia on the floor of congress, lie sought

the friendship of nearly every leading statesman of his commonwealth, and every

one seemed glad to call him a friend."

On 1 March, 1784, the Virginia delegates presented to congress a deed that

ceded to the United States Virginia's claim to the northwest

territory, and soon afterward Jefferson presented his memorable plan for the

temporary government of all the western possessions of the United States from

the southern boundary (lat. 31. N.) to the Lake of the Woods. From that time

until its settlement by the ordinance of 13 July, 1787, this question was of

paramount importance. Twice within a few months Monroe crossed the Alleghenies

for the purpose of becoming acquainted with the actual condition of the country.

One of the fruits of his western observations was a memoir, written in 1786, to

prove the rights of the people of the west to the free navigation of the

Mississippi.

Toward the close of 1784 Monroe was selected as one of nine judges to decide

the boundary dispute between Massachusetts and New York. He resigned this place

in May, 1786, in consequence of an acrimonious controversy in which he became

involved. Both the states that were at difference with each other were at

variance with Monroe in respect to the right to navigate the Mississippi, and

lie thought himself thus debarred from being acceptable as an umpire to either

of the contending parties, to whom he owed his appointment.

In the congress of 1785 Monroe was interested in the regulation of commerce

by the confederation, and he certainly desired to secure that result: but he was

also jealous of the rights of the southern states, and afraid that their

interests would be overbalanced by those of the north. His policy was therefore

timid and dilatory. A report upon the subject by the committee, of which he was

chairman, was presented to congress, 28 March, 1785, and led to a long

discussion, but nothing came of it. The weakness of the confederacy grew more

and more obvious, and the country was drifting toward a stronger government. But

the measures proposed by Monroe were not entirely abortive. Says John

Q. Adams: "They led first to the partial convention of delegates

from five states at Annapolis in September, 1786, and then to the general

convention at Philadelphia in 1787, which prepared and proposed the constitution

of the United States. Whoever contributed to that event is justly entitled to

the gratitude of the present age as a public benefactor, and among them the name

of Monroe should be conspicuously enrolled."

According to the principle of rotation then in force, Monroe's congressional

service expired in 1786, at the end of a three years' term. He then intended to

make his home in Fredericksburg, and to practice law, though he said he should

be happy to keep clear of the bar if possible. But it was not long before he was

again called into public life. He was chosen at once a delegate to the assembly,

and soon afterward became a member of the Virginia convention to consider the

ratification of the proposed constitution of the United States, which assembled

at Richmond in 1788. In this convention the friends of the new constitution were

led by James Madison, John

Marshall, and Edmund Randolph.

Patrick Henry was their chief opponent, and

James Monroe was by his side, in company with William Grayson and George

Mason. In one of his speeches, Monroe made an elaborate historical argument,

based on the experience of Greece, Germany, Switzerland, and New England,

against too firm consolidation, and he predicted conflict between the state and

national authorities, and the possibility that a president once elected might be

elected for life. In another speech he endeavored to show that the rights of the

western territory would be less secure under the new constitution than they were

under the confederation. He finally assented to the ratification on condition

that certain amendments should be adopted. As late as 1816 he recurred to the

fears of a monarchy, which he had entertained in 1788, and endeavored to show

that they were not unreasonable.

Under the new constitution the first choice of Virginia for senators fell

upon Richard Henry Lee and William Grayson.

Tim latter died soon afterward, and Monroe was selected by the legislature to

fill the vacant place. He took his seat in the senate, 6 December, 1790, and

held the office until May, 1794, when he was sent as envoy to France. Among the

Anti-Federalists he took a prominent stand, and was one of the most determined

opponents of the administration of Washington. To Hamilton he was especially

hostile. The appointment of Gouverneur Morris

to be minister to France, and of John Jay to be

minister to England, seemed to him most objectionable. Indeed, he met all the

Federalist attempts to organize a strong and efficient government with

incredulity or with adverse criticism. It was therefore a great surprise to him,

as well as to the public, that, while still a senator, he was designated the

successor of Morris as minister to France.

For this difficult place he was not the first choice of the president, nor

the second: but he was known to be favorably disposed toward the French

government, and it was thought that he might lead to the establishment of

friendly relations with that power, and, besides, there is no room to doubt that

Washington desired, as , John Quincy Adams has said, to hold the balance between

the parties at home by appointing Jay, the Federalist, to the English mission,

and Monroe, the Republican, to the French mission. It was the intent of the

United States to avoid a collision with any foreign power, but neutrality was in

danger of being considered an offence by either France or England at any

moment.

Monroe arrived in Paris just after the fall of Ropespierre, and in the

excitement of the day he did not at once receive recognition from the committee

of public safety. He therefore sent a letter to the president of the convention,

and arrangements were made for his official reception, 15 August, 1794. At that

time he addressed the convention in terms of great cordiality, but his

enthusiasm led him beyond his discretion, he transcended the authority that had

been given to him, and when his report reached the government at home Randolph

sent him a dispatch, " in the frankness of friendship," criticizing

severely the course that the plenipotentiary had pursued. A little latex the

secretary took a more conciliatory tone and Monroe bellowed he never would have

spoken so severely if all the dispatches from Paris had reached the United

States in due order.

The residence of Monroe in France was a period of anxious responsibility,

during which he did not succeed in recovering the confidence of the authorities

at home. When Pickering succeeded Randolph in the department of state. Monroe

was informed that he was superseded by the appointment of Charles C. Pinckney.

The letter of recall was dated 22 August. 1796. On his return he published a

pamphlet of 500 pages, entitled "A View of the conduct of the

Executive" (Philadelphia, 1797) in which he printed his instructions,

correspondence with the French and United States governments, speeches, and

letters received from American residents in Paris. This publication made a great

stir. Washington, who had then retired from public life. appears to have

remained quiet under the provocation, but he wrote upon his copy of the

"View" animadversions that have since been published.

Party feeling, already excited, became fiercer when Monroe's book appeared,

and personalities that have now lost their force were freely uttered on both

sides. Under these circumstances Monroe became the hero of the Anti-Federalists,

and was at once elected governor of Virginia. He held the office from 1799 till

1802. The most noteworthy occurrence during his administration was the

suppression of a servile insurrection by which the city of Richmond was

threatened. Monroe's star continued in the ascendant. After Thomas Jefferson's

election to the presidency in 1801, an opportunity occurred for returning Mr.

Monroe to the French mission, from which he had been recalled a few years

previously. There were many reasons for believing that the United States could

secure possession of the territory beyond the Mississippi belonging to France.

The American minister in Paris, Robert R Livingston, had already opened the

negotiations, and Monroe was sent as an additional plenipotentiary to second,

with his enthusiasm and energy, the effort that had been begun. By their joint

efforts it came to pass that in the spring of 1803

a treaty was signed by which France gave up to the United States for a

pecuniary consideration the vast region then known as Louisiana. Livingston

remarked to the plenipotentiaries after the treaty was signed; " We have

lived long, but this is the noblest work of our lives."

The story of the negotiations that terminated in this sale is full of

romance. Bonaparte, Talleyrand, and Marbois

were the representatives of France. Jefferson. Livingston, and Monroe

guided the interests of the United States. The French were in need of money and

the Americans could afford to pay well for the control of the entrance to the

Mississippi. England stood ready to seize the coveted prize. The moment was

opportune; the negotiators on both sides were eager for the transfer. It did not

take long to agree upon the consideration of 80,000,000 francs as the

purchase-money, and the assent of Bonaparte was secured. "I have given

to England," he said, exultingly, "a maritime rival that will

sooner or later humble her pride."

It is evident that the history of the United States has been largely

influenced by this transaction, which virtually extended the national domain

from the mouth of the Mississippi river to the mouth of the Columbia. Monroe

went from Paris to London, where he was accredited to the court of St. James,

and subsequently went to Spain in order to negotiate for the cession of Florida

to the United States. But he was not successful in this and returned to London,

where, with the aid of William Pinckney, who was sent to re-enforce his efforts,

he concluded a treaty with Great Britain after long negotiations frequently

interrupted. This treaty failed to meet the expectations of the United States in

two important particulars--it made no provisions against the impressments of

seamen, and it secured no indemnity for loss that Americans had incurred in the

seizure of their goods and vessels. Jefferson was so dissatisfied that he would

not send the treaty to the senate.

Monroe returned home in 1807 and at once drew up an elaborate defense of his

political conduct. Matters were evidently drifting toward war between Great

Britain and the United States. Again the disappointed and discredited

diplomatist received a token of popular approbation. He was for the third time

elected to the assembly, and in 1811 was chosen for the second time governor of

Virginia. He remained in this office but a short time, for he was soon called by

Madison to the office of secretary of state. He held the portfolio during the

next six years, from 1811 to 1817. In 1814-'15 he also acted as secretary of

war. While he was a member of the cabinet of Madison, hostilities were begun

between the United States and England. The public buildings in Washington were

burned, and it was only by the most strenuous measures that the progress of the

British was interrupted.

Monroe gained much popularity by the measures that he took for the protection

of the capital and for the enthusiasm with which he prosecuted the war measures

of the government Monroe had now held almost every important station except that

of president to which a politician could aspire. He had served in the

legislature of Virginia, in the Continental congress, and in the senate of the

United States. He had been a member of the convention that considered the

ratification of the constitution, twice he had served as governor, twice he had

been sent abroad as a minister, and he had been accredited to three great

powers. He had held two places in the cabinet of Madison. With the traditions of

those days, which regarded experience in political affairs a qualification for

an exalted station, it was most natural that Monroe should become a candidate

for the presidency. Eight years previously his fitness for the office had been

often discussed.

Now, in 1816, at the age of fifty-nine years, almost exactly the age at which

Jefferson and Madison attained the same position, he was elected president of

the United States, receiving 183 votes in the electoral college against 34 that

were given for RufusKing, the candidate of the

Federalists. He continued in this office until 1825. His second election in 1821

was made with almost complete unanimity, but one electoral vote being given

against him. Daniel D. Tompkins was vice-president during both presidential

terms. John Quincy Adams, John C. Calhoun, William

H. Crawford, and William Wirt, were members of the cabinet during his entire

administration. The principal subjects that engaged the attention of the

president were the defenses of the Atlantic seaboard, the promotion of internal

improvements, the conduct of the Seminole war, the acquisition of Florida, the

Missouri compromise, and the resistance to foreign interference in American

affairs, formulated in a declaration that is called the "Monroe

doctrine."

Two social events marked the beginning and the end of his administration:

first, his ceremonious visit to the principal cities of the north and south; and

second, the national reception of the Marquis

de Lafayette who came to this country as the nation's guest The purchase of

the Floridas was brought to a successful issue, 22 February, 1819 by a treaty

with Spain, concluded at Washington, and thus the control of the entire Atlantic

and Gulf seaboard, from the St. Croix to the Sabine, was secured to the United

States. Monroe's influence in the controversies that preceded the Missouri

compromise does not appear to have been very strong. He showed none of the

boldness which Jefferson would have exhibited under similar circumstances. He

took more interest in guiding the national policy with respect to internal

improvements and the defense of the seaboard. He vetoed the Cumberland road

bill, 4 May, 1822, on the ground that congress had no right to execute a system

of internal improvement ; but he held that if such powers could be secured by

constitutional amendment good results would follow. Even then he held that the

general government should undertake only works of national significance, and

should leave all minor improvements to the separate states.

There is no measure with which the name of Monroe is connected so important

as his enunciation of "the Monroe doctrine." The words of this

famous utterance constitute two paragraphs in the president's message of 2

December, 1823. In the first of these paragraphs he declares that the

governments of Russia and Great Britain have been informed that the American

continents henceforth are not to be considered subjects for future colonization

by any European powers. In the second paragraph he says that the United States

would consider any attempt on the part of the European powers to extend their

system to any portion of this hemisphere as dangerous to our peace and safety.

He goes further, and says that if the governments established in North and South

America who have declared their independence of European control should be

interfered with by any European power, this interference would be regarded as

the manifestation of unfriendly disposition to the United States. These

utterances were addressed especially to Spain and Portugal. They undoubtedly

expressed the dominant sentiments of the people of the United States at the time

they were uttered, and, moreover, they embodied a doctrine which had been

vaguely held in the days of Washington, and from that time to the administration

of Monroe had been more and more clearly avowed.

It has received the approval of successive administrations and of the

foremost publicists and statesmen. The peace and prosperity of America have been

greatly promoted by the declaration, almost universally assented to, that

European states are not to gain new dominion in America. For convenience of

reference the two passages of the rues-sage are here quoted: "At the

proposal of the Russian imperial government, made through the minister of the

emperor residing here, full power and instructions have been transmitted to the

minister of the United States at St. Petersburg, to arrange, by amicable

negotiation, the respective rights and interests of the two nations on the

northwest coast of this continent. A similar proposal had been made by his

imperial majesty to the government of Great Britain, which has likewise been

acceded to. The government of the United States has been desirous, by this

friendly proceeding, of manifesting the great value which they have invariably

attached to the friendship of the emperor, and their solicitude to cultivate the

best understanding with his government. In the discussions to which this

interest has given rise, and in the arrangements by which they may terminate,

the occasion has been judged proper for asserting, as a principle in which the

rights and interests of the United States are involved, that the American

continents, by the free and independent condition which they have assumed and

maintain, are henceforth not to be considered as subjects for future

colonization by any European power .... We owe it, therefore, to candor, and to

the amicable relations existing between the United States and those powers, to

declare that we should consider any attempt on their part to extend their system

to any portion of this hemisphere as dangerous to our peace and safety. With the

existing colonies or dependencies of any European power we have not interfered,

and shall not interfere. But with the governments who have declared their

independence and maintained it, and whose independence we have, on great

consideration and on just principles, acknowledged, we could not view any

interposition for the purpose of oppressing them, or controlling in any other

manner their destiny, by any European power, in any other light than as the

manifestation of an unfriendly disposition toward the United States."

At the close of Monroe's second term as president he retired to private life,

and during the seven years that remained to him resided part of the time at Oak

Hill, Loudon County, Virginia, and part of the time in the city of New York. The

illustration above represents both the old and the new Oak Hill mansions. He

accepted the office of regent in the University of Virginia in 1826 with

Jefferson and Madison. He was asked to serve on the electoral ticket of Virginia

in 1828, but declined on the ground that an ex-president should not be a

party-leader. He consented to act as a local magistrate, however, and to become

a member of the Virginia constitutional convention. The administration of Monroe

has often been designated as the "era of good feeling."

Schouler, the historian, has found this heading on an article that appeared

in the Boston Centinel of 12 July, 1817. it is, on the whole, a suitable phrase

to indicate the state of political affairs that succeeded to the troublesome

period of organization and preceded the fearful strains of threatened disruption

and of civil war. One idea is consistently represented by Monroe from the

beginning to the end of his public life--the idea that America is for Americans,

that the territory of the United States is to be protected and enlarged, and

that foreign intervention will never be permitted. In his early youth Monroe

enlisted for the defense of American independence. He was one of the first to

perceive the importance of free navigation upon the Mississippi: he negotiated

with France and Spain for the acquisition of Louisiana and Florida; he gave a

vigorous impulse to the second war with Great Britain in de-fence of our

maritime rights when the rights of a neutral power were endangered; and he

enunciated a dictum against foreign interference which has now the force of

international law. Judged by the high stations he was called upon to fill, his

career was brilliant; but the writings he has left in state papers and

correspondence are inferior to those of Jefferson, Madison, Hamilton, and others

of his contemporaries. He is rather to be honored as an upright and patriotic

citizen who served his party with fidelity and never condescended to low and

unworthy measures. He deserved well of the country, which he served faithfully

during his career. After his retirement from the office of president he urged

upon the government the judgment of unsettled claims which he presented for

outlays made during his prolonged political services abroad and for which he had

never received adequate remuneration.

During the advance of old age his time was largely occupied in

correspondence, and he undertook to write a philosophical history of the origin

of free governments, which was published long after his decease. While attending

congress, Monroe married, in 1786, a daughter of Lawrence Kortright, of New

York. One of his two daughters, Eliza., married George Hay, of Virginia, and the

other, Maria, married Samuel L. Gouverneur of New York. A large number of

manuscripts, including drafts of state papers, letters addressed to Monroe, and

letters from him, have been preserved. Most of these have been purchased by

congress and are preserved in the archives of the state department ; others are

still held by his descendants. Schouler, in his "History of the United

States," has made use of this material to advantage, particularly in

his account of the administrations of Madison and Monroe, which he has treated

in detail. Bancroft, in his "History of the Constitution,"

draws largely upon the Monroe papers, many of which he prints for the first

time. The eulogy of John Quincy Adams his (Boston diary 1831) afford and the

best contemporary view of Monroe's characteristics as a statesman.

Jefferson, Madison, Webster, Calhoun, and Benton have left their appreciative

estimates of his character The remains of James Monroe were buried in Marble

cemetery, Second street, between First and Second avenues, New York, but in 1858

were taken to Richmond, Virginia, and there re-interred on the 28th of April, in

Hollywood. (See illustration above.) See Samuel P. Waldo's "Tour of James

Monroe through the Northern and Eastern States, with a Sketch of his Life"

(Hartford, 1819); " Life of James Monroe, with a Notice of his

Administration," by John Quincy Adams (Buffalo, 1850) : "Concise

History of the .Monroe Doctrine," by George F. Tucker (Boston, 1885): and

Daniel C. Gilman's life of Monroe, in the "American Statesmen " series

(Boston, 1883). In the volume last named is an appendix by J. F. Jameson, which

gives a list of writings pertaining to Monroe's career and to the Monroe

doctrine. Monroe's portrait by Stuart is in the possession of Thomas J.

Coolidge, and that by Vanderlyn is in the city-hall, New York, both of which

have been engraved.--

His wife, Elizabeth Kortright, born in New

York city in 1768; died in Loudon county, Virginia, in 1830, was the daughter of

Lawrence Kortright, a captain in the British army. She married James Monroe in

1786, accompanied him in his missions abroad in 1794 and 1803, and while he was

United States minister to France she effected the release of Madame de

Lafayette, who was confined in the prison of LaForce, hourly expecting to be

executed. On the accession of her husband to the presidency, Mrs. Monroe became

the mistress of the White House; but she mingled little in society on account of

her delicate health. She is described by a contemporary writer as "an

elegant and accomplished woman, with a dignity of manner that peculiarly fitted

her for the station." The above vignette is copied from the only

portrait that was ever made of Mrs. Monroe, which was executed in Paris in 1796

His nephew, James Monroe, soldier, in Albemarle county, Virginia, 10

September, 1799; died in Orange, New Jersey, 7 September, 1870, was a son of the

president's elder brother, Andrew. He was graduated at the United States

military academy in 1815, assigned to the artillery corps, and served in the war

with Algiers, in which he was wounded while directing part of the quarter-deck

guns of the "Guerridre" in an action with the "Mashouda"

off Cape de Gata, Spain. He was aide to General Winfield

Scott in 1817-'22, became 1st lieutenant of the 4th artillery on the

reorganization of the army in 1821, and served on garrison and commissary duty

till 1832, when he was again appointed Gem Scott's aide on the Black Hawk

expedition, but did not reach the seat of war, owing to illness. He resigned his

commission on 30 September, 1832, and entered politics, becoming an alderman of

New York city in 1833, and president of the board in 1834. In 1836 he declined

the appointment of aide to Governor William L. Marcy. He was in congress in

1839-'41, and was chosen again in 1846, but his seat was contested, and congress

ordered a new election, at which he refused to be a candidate. During the

Mexican war he was active in urging the retention in command of General Scott.

In 1850-'2 he was in the New York legislature, and in 1852 was an earnest

supporter of his old chief for the presidency. After the death of his wife in

that year he retired from politics, and spent much of his time at the Union

club, of which he was one of the earliest members. Just before the civil war he

visited Richmond, and, by public speeches and private effort, tried to prevent

the secession of Virginia, and in the struggle that followed he remained a firm

supporter of the National government. He much resembled his uncle in personal

appearance.

Presidential

Libraries

Rutherford

B. Hayes Presidential Center

McKinley

Memorial Library

Herbert

Hoover Presidential Library and Museum - has research collections containing

papers of Herbert Hoover and other 20th century leaders.

Franklin

D. Roosevelt Library and Museum - Repository of the records of President

Franklin Roosevelt and his wife Eleanor Roosevelt, managed by the National

Archives and Records Administration.

Harry

S. Truman Library & Museum

Dwight

D. Eisenhower Presidential Library - preserves and makes available for

research the papers, audiovisual materials, and memorabilia of Dwight and Mamie

D. Eisenhower

John

Fitzgerald Kennedy Library

Lyndon

B. Johnson Library and Museum

Richard

Nixon Library and Birthplace Foundation

Gerald

R. Ford Library and Museum

Jimmy

Carter Library

Ronald Reagan Presidential Library

- 40th President: 1981-1989.

George

Bush Presidential Library