WYMAN, Morrill, physician,

born in Chelmsford, Massachusetts, 25 July, 1812. He was graduated at Harvard in

1833, and at the medical department in 1837. Meanwhile he served as assistant

engineer on the Boston and Worcester railroad during 1833, and during 1836 was

house physician to the Massachusetts general hospital. On the completion of his

medical studies he settled in Cambridge, where he has since followed his

profession. In 1853 he became adjunct professor of the theory and practice of

medicine in Harvard, but he relinquished this chair after three years'

occupation, he invented in 1850 an instrument for removing fluids from the

cavities of the body, especially the chest, consisting essentially of a trocar

and cannula of a very small diameter fitted to an exhausting-syringe. By its use

an operation, which was previously considered dangerous, and was often fatal,

has been rendered effectual, safe, and almost painless. Dr. Wyman is a member of

the Massachusetts medical society and of the American academy of arts and

sciences. In 1875 he was elected an overseer of Harvard, and he has since been

re-elected. The degree of LL.D. was given him by Harvard in 1885. He has

published a "Memoir of Daniel Treadwell" (Cambridge, 1888), and

in book-form "A Practical Treatise on Ventilation" (Cambridge,

1846) ; " Progress in School Discipline" (1868): and "Autumnal

Catarrh" (New York, 1872).

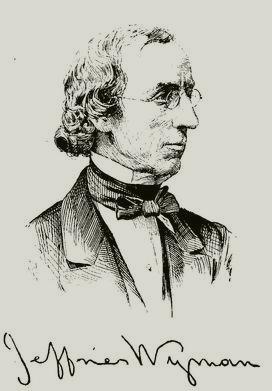

Jeffries

Wyman

WYMAN, Jeffries, his brother,

comparative anatomist, born in Chelmsford, Massachusetts, 11 August, 1814; died

in Bethlehem. New Hampshire, 4 September, 1874, was graduated at Harvard in

1833, and at the medical school in 1837. In 1836 he was appointed house

physician in the Massachusetts a general hospital he settled in Boston, became

demonstrator of anatomy under Dr. John C. Warren, was appointed curator of the

newly founded Lowell institute in 1839, and in 1840-'1 delivered a course of

twelve lectures on comparative anatomy and physiology. With the money that he

derived from this source he went to Europe and studied human anatomy at the

School of medicine, and comparative anatomy at the Jardin des plantes in Paris,

after which he spent some time at the Royal college of surgeons in London. He

returned to Boston in 1843, and in the autumn accepted the professorship of

anatomy and physiology in Hampden Sidney college, Virginia, where he continued

for five years, except during the summers which he spent in Boston. In 1847 he

was appointed to the chair of anatomy in Harvard, succeeding Dr. John C. Warten,

remained at the head of the department until his death, and during all the time

he was noted as a clear and conscientious teacher and lecturer. He at once began

the formation of a Museum of comparative anatomy, which was one of the earliest

in this country, and is intended to show some of the important modifications of

the organs of animals in connection with the physiological processes of which

they are the seat, as well as the conditions of embryological development and

the successive phases through which the embryo passes. After his death it became

the property of the Boston society of natural history.

In 1849 he delivered a second course of lectures before the Lowell

institute on "Comparative Physiology," which gained for him a

high rank among American anatomists and physiologists. In 1856 he visited,

Surinam, Guiana, and penetrated in canoes far into the interior, making

important researches upon the ground, and enriching his museum with animals of

great anatomical interest. He made a voyage to La Plata river in 1858-'9,

ascended the Uruguay and the Parana in a small iron steamer, and then crossed

the pampas to Mendoza, and the Cordilleras to Santiago and Valparaiso, whence he

returned by way of the Peruvian coast and the Isthmus of Panama. His

investigations were first in the domain of comparative anatomy and physiology

and then in paleontology, but with his great knowledge of the branches he was

able in later years to concentrate his maturer powers on investigations in

ethnology, and more especially in archaeology. Of his early studies, that "On

the External Characters, Habits, and Osteology of the Gorilla" (1847)

was the first, scientific description of that animal, whose specific name of

gorilla was bestowed on it by Dr. Wyman. His paper "In the Nervous

System of the Bull-Frog," published by the Smithsonian institution

(1853), is said to be the "clearest introduction to the most complex of

animal structures" that was issued up to that time.

He was also the author of a series of papers on the anatomy of the blind

fish of the Mammoth cave. To this subject, and to the comparative anatomy of the

higher apes, he returned from time to time as material was afforded. He exposed

the fraudulent nature of the skeleton called the Hydrachus Sillimani, alleged to

be that of an extinct sea-serpent. His "Observations on the Development of

the Skate" (1864) showed most conclusively that it ranks higher than the

shark, since the latter retains through life a general form resembling one of

the stages through which the former passes during its development. One of his

most interesting researches was "Observations and Experiments on Living

Organisms in Heated Water" (1867), which showed that no life appeared

in water that is boiled more than five hours. Although reluctant to express an

opinion on the subjects of spontaneous generation and the theory of descent,

still his experiments convinced him that the former does not exist, and his

teaching was favorable to the latter. He was a member of the faculty of the

Museum of comparative zoology from the first, and he taught comparative anatomy

in the Lawrence scientific school of Harvard. On the foundation of the Peabody

museum of American ethnology and archaeology at Cambridge in 1866, he was named

as one of the seven trustees, and was chosen its curator by his associates.

Under these circumstances his work naturally tended toward archaeology, and,

spending his winters in Florida, he was led to investigate the ancient

shell-heaps there. In these he found evidences of prehistoric peoples, one of

which was cannibal in its habits, he also discovered and studied similar

refuse-piles along the coast of New England. He published several papers on this

subject in the "American Naturalist" and in the "Reports

of the Trustees of the Peabody Museum " (7 vols., Cambridge, 1867-'74),

but his results are most fully given in a posthumous memoir on the "Fresh-water

Shell-mounds of the St. John's River, Florida" (Salem, 1875).

Professor Wyman was a member of the Linnaan society of London, and of the

Anthropological institute of Great Britain and Ireland, and, besides membership

in various other societies in this country, was a fellow and councilor of the

American academy of arts and sciences. In 1856 he was chosen president of the

American association for the advancement of science, but he was unable to be

present at the subsequent meeting. His relations with the Boston society of

natural history were very close. From 1839 to 1841 he was its recording

secretary, and then successively curator of ichthyology and herpetology and

comparative anatomy, and from 1856 to 1870 he was its president. He was one of

the corporate members of the National academy of sciences, named by act of

congress in 1863, and, although he soon resigned, his name was retained on the

list of honorary members, his bibliography includes 175 titles, a full list of

which, compiled by Alpheus S. Packard, accompanies the sketch of Dr. Wyman by

him, which is published in the "Biographical Memoirs of the National

Academy of Sciences" (vol. ii., Washington, 1886). Asa Gray, Oliver

Wendell Holmes, S. Weir Mitchell, Frederick W. Putnam, and Burr G. Wilder

published sketches of his life, and James Russell Lowell a memorial sonnet.