LINCOLN, Benjamin - A Klos Family Project - Revolutionary War General

Click on an image to view full-sized

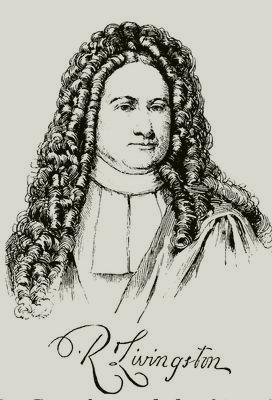

Robert Livingston

LIVINGSTON, Robert, first

ancestor of the family in America, born in Antrum, Scotland, 13 December, 1654;

died in Albany, New York, 20 April, 1725. He was the son of John Livingston, a

Scottish Presbyterian divine, born in 1603, who was banished in 1663 for

non-conformity and went to Rotterdam, where he died in 1672. Among the early

members of the family was Mary Livingston, who went to France with Mary Stuart

as one of her maids of honor. Robert emigrated to Charlestown, Massachusetts, in

April, 1673, settled in Albany, and as early as 1675 became secretary of the

commissaries, which office he held until Albany became a city in 1686.

Subsequently he continued to hold the similar office of town clerk until 1721.

Mr. Livingston was a member of the colonial assembly from the city and county of

Albany in 1711, and after 1716 was returned from his manor till 1725, becoming

speaker in 1718.

He acquired great influence over the Indians, retaining the office of

secretary of Indian affairs, which he received from Governor Edmund Andros for a

long series of years. In 1686 he received from Governor Thomas Dongan a grant of

a large tract of land, which in 1715 was confirmed by a royal charter from

George I., erecting the manor and lordship of Livingston, with the privilege of

holding a court leer and a court baron, and with the right of advowson to all

the churches within its boundaries. This tract era-braced large parts of what

are now the counties of Dutchess and Columbia, New York, and is still known as

the Livingston manor, though most of it has long since passed out of the hands

of the family. It was through his influence that means were procured to fit out

the ship with ~ which Captain William Kidd (q. v.) undertook to restrain the

excesses of pirates. He married in 1679 Alida, widow of the Reverend Nicholas

Van Rensselaer and daughter of Philip Pietersen Schuyler, by whom he had three

sons, Philip, Robert, and Gilbert.--

Robert's son, Philip Livingston, second

lord of the manor, born in Albany, 9 July, 1686; died in New York city, 4

February, 1749, was for some time deputy secretary of Indian affairs under his

father, and, on the resignation of the latter in 1722, succeeded to the

secretaryship. In 1709 he was a member of the provincial assembly from the city

and county of Albany, and he was also county clerk in 1721-'49. Livingston was a

member of the provincial council till his death.

He married Catherine Van Brugh, of Albany, and during the latter part of his

life entertained with great magnificence at his three residences in New York,

Albany, and the manor. His eldest daughter, Sarah, married William Alexander,

Lord Stirling, and his son, Robert, became the third and last lord of the manor.

-Philip's son, Peter Van Brugh Livingston, merchant, born in Albany in

October, 1710; died in Elizabethtown, New Jersey. 28 December, 1792, was

graduated at Yale in 1731, and soon afterward settled in New York, where he

erected a large mansion on the east side of what is now Hanover square, with

grounds extending to East river. He engaged in the shipping business with

William Alexander, Lord Stirling, whose sister, Mary, he married in November,

1739, and one of the transactions in which he was engaged was the furnishing of

supplies to Governor William Shirley's expedition to Acadia in 1755. For many

years he was a member of the council of the province, and he was also one of the

committee of one hundred. He was a delegate to the 1st and 2d provincial

congresses of New York in 1775-'6, being president of the 1st congress. In 1776

he was made treasurer of the congress, and held that office for two years, also

participating in all of the pre-Revolutionary measures. Late in life he removed

to Elizabethtown, New Jersey, where he spent his last years. He was a firm

Presbyterian, and in 1748 was named one of the original trustees of the College

of New Jersey, holding that office until 1761. John

Adams spoke of him as "an old man extremely stanch in the cause and

very sensible."

Another son of Philip, Philip Livingston,

signer of the Declaration of

Independence, born in Albany, New York, 15 January, 1716; died in York,

Pennsylvania, 12 June, 1778, was graduated at Yale in 1737, and in 1746 was

referred to as one of the fifteen persons in the colony that possessed a

collegiate education. After graduation he engaged in business successfully as an

importer in New York city, and Sir Charles Hardy said of him in 1755 that "among

the considerable merchants in this city no one is more esteemed for energy,

promptness, honesty, and public spirit, than Philip Livingston."

He was elected one of the seven aldermen of New York in September, 1754, and

held that office with the approbation of his constituents continuously for nine

years. He was also returned to the provincial assembly as member from New York City,

and so continued by re-election until its dissolution in January, 1769. During

his legislative career he identified himself with the rising opposition to the

arbitrary measures of the mother country and was active in the conduct of public

business. He was one of the committee of correspondence with Edmund Burke, then

the agent for the colony in England, and the great knowledge of colonial affairs

that was shown by Mr. Burke in the house of commons was derived from this

source.

In September, 1764, he drew up a spirited address to Lieutenant-Governor

Cadwallader Colden, in which the boldest language was employed to express the

hopes of the colonists for freedom from taxation, and he was a delegate to the

state pact congress in October, 1765. He was chosen speaker of the provincial

assembly at the last session that he attended, and declined a re-election from

the city, but was returned for his brother's manor of Livingston, and took his

seat in April. A month later he was unseated by the Tory majority on the plea

that he was a non-resident.

Mr. Livingston was chosen a member of the first Continental congress which

met in Philadelphia in September, 1774, and continued a member of that body

until his death. At the first convention he was appointed one of the committee

to prepare an address to the people of Great Britain, and later was one of the

New York delegates that signed the Declaration

of Independence. Meanwhile he was also active in local affairs, holding the

office of president of the provincial congress in April, 1775, and in February,

1776, he was again chosen a member of the general assembly. It was at his house

on Brooklyn heights that Washington held the

council of war in August, 1776, that decided on the retreat from Long Island.

This mansion, shown in the illustration on the top of this page, was situated on

what is now Hicks street, a little to the south of Joralemon. It was on the

highest point of the property, which included about forty acres, and commanded a

magnificent view of New York harbor. The house itself was elegantly finished,

containing exquisitely carved Italian marble mantels, and was magnificently

furnished.

During the Revolutionary war the

British took possession of the building and converted it into a naval hospital.

The property soon went to decay, and the old mansion was ultimately destroyed by

fire. In May, 1777, he was chosen a state senator, and in September he attended

the first meeting of the first legislature of the state of New York. He was then

elected one of the first delegates to congress under the new confederation. Mr.

Livingston was active in the movements tending to develop the interests of New

York city. He was one of the founders of the New York society library in 1754

and of the Chamber of commerce in 1770, one of the first governors of the New

York hospital, chartered in 1771, and one of the earliest advocates of the

establishment of Kings (now Columbia) college. In 1746 he aided in founding the

professorship of divinity that bears his name in Yale, and was one of the

contributors to the building of the first Methodist church in the United

States.

-Another son of Philip, William Livingston,

governor of New Jersey, born in Albany, New York, 30 November, 1723; died in

Elizabethtown, New Jersey, 25 July, 1790, was the protégé of his maternal

grandmother, Sarah Van Brugh, with whom his boyhood days were spent. Before he

was fourteen years old he lived an entire year among the Mohawk Indians, under

the care of an English missionary. He was graduated at Yale in 1741, at the head

of his class, and then began the study of law in the office of James Alexander,

completing his course under William Smith.

In October, 1748, he was admitted to the bar, and soon became one of the

leaders in his profession, acquiring the name of the Presbyterian lawyer. He was

elected to the provincial legislature from his brother's manor of Livingston,

and served for three years, meanwhile also continuing his practice. In 1760 he

purchased property near Elizabethtown, New Jersey, and there erected a country

seat which is celebrated as "Liberty Hall," and in May, 1772,

having reduced his professional practice, he removed to that place with his

family. It was of this residence, shown in the illustration on page 743, that

his daughter Susan said, "We are going into cloister seclusion,"

as she bade adieu to her city friends, but "the toilsome and muddy way

from New York was kept well trodden by brilliant and ever welcome guests,"

who came to pay their addresses to the four young ladies.

Among their visitors was John Jay, who in 1774

married Miss Sarah V. B. Livingston from this mansion, and to it came also Alexander

Hamilton, a boy from the West Indies, with letters to Governor Livingston

from Dr. Hugh Knox. It had an eventful history during the Revolutionary

war, and more than once attempts were made to burn it. The stairs still show

the cuts that were left by the angry Hessians when they were baffled in their

attempts to capture its owner.

After the war its graceful hospitalities were renewed, and here in May, 1789,

Mrs. Washington was entertained overnight

while on her journey to meet the president, after his inauguration. The hall was

decorated with flowers, and a brilliant assemblage of distinguished guests

gathered to do her honor. In the morning Washington himself came out to escort

her to the city.

His retirement was soon interrupted by the progress of public events, and he

was elected a deputy for the province of New Jersey to the 1st Continental

congress in July, 1774, and reelected to the 2d and 3d congresses. In June,

1776, he left congress for Elizabethtown, to assume the duties of

brigadier-general and commander-in-chief of the New Jersey militia, an invasion

by the British being feared. This duty prevented his return to Philadelphia, and

explains the absence of his name from the signers of the Declaration

of Independence.

In August he was elected first governor of the state of New Jersey, and after

resigning his military command he continued in office until his dearth. Governor

Livingston, in his message in 1777 to the assembly, recommended the abolition of

slavery, and in 1786, through his influence, caused the passage of an act

forbidding the importation of slaves, he himself liberating those in his own

possession, with the resolution never to own another. During the occupancy of

New Jersey by British troops he filled his office with great efficiency, as is

shown by Washington's writings. Several expeditions were made for the purpose of

kidnapping him, but he was always fortunate in escaping. Governor Livingston was

known as the "Itinerant Dey of New Jersey," "the Knight of the

most honorable Order of Starvation and Chief of the Independents," and

the "Don Quixote of the Jerseys," on account of his being very

tall and thin. A "female wit" dubbed him "the whipping

post."

In 1787 he was a delegate to the convention that framed the United

States constitution, and he had previously declined the appointment of

commissioner to superintend the construction of the Federal buildings, and that

of minister to Holland. He received the degree of LL. D. from Yale in 1788, was

among the original trustees of the New York society library, and in 1751 was

made one of the trustees of Kings (now Columbia) college, but declined to

qualify when he found that the president must be a clergyman of the Church of

England. For some time he was president of the "Moot," a club

of lawyers formed in 1770 and well known in the early history of New York city,

and he was also a member of the American philosophical society and of the

American academy of arts and sciences. President Timothy Dwight, of Yale, says

of him, "The talents of Governor Livingston were very various. His

imagination was brilliant, his wit sprightly and pungent, his understanding

powerful, his taste refined, and his conceptions bold and masterly. His views of

political subjects were expansive, clear, and just. Of freedom, both civil and

religious, he was a distinguished champion."

Governor Livingston began the publication in 1752 of "The Independent

Reflector," a weekly political and miscellaneous journal, in which he

opposed the establishment of an American episcopate and the incorporation of an

Episcopal college in New York. It was discontinued after the publication of

fifty-two numbers. He wrote largely for the newspapers, and, besides numerous

political tracts, published "Philosophic Solitude, or the Choice of a Rural

Life," a poem (New York, 1747); "A Funeral Elogium on the Reverend

Aaron Burr" (1757); "A Soliloquy" (1770); and, with

William Smith, Jr., "A Digest of the Laws of New York--1691-1762"

(1752-'62). See "Life and Letters of William Livingston," by

Theodore Sedgwick, Jr. (New York, 1833).

--William's son, Henry Brockholst

Livingston, lawyer, born in New York city, 26 November, 1757; died in

Washington, D. C., 19 March, 1823, was graduated at Princeton in 1774, at the

beginning of the Revolutionary war entered the American army with the grade of

captain, and, being selected by General Philip Schuyler as one of his aides, was

attached to the northern department with the rank of major. Subsequently he was

aide to General Arthur St. Clair during the

siege of Ticonderoga, and was with Benedict Arnold

at the surrender of Burgoyne's army in October,

1777. Later he served again with General Schuyler,

and obtained the rank of lieutenant-colonel. In 1779 he accompanied his

brother-in-law, John Jay, to Spain, as private

secretary. On his return voyage in 1782 he was captured by a British vessel, and

on reaching New York was thrown into prison. He was liberated on the arrival of

Sir Guy Carleton, who sent him home to his father, saying that he came to

conciliate and not to fight.

Livingston then went to Albany, where he began the study of law with Peter

Yates, and in 1783 was admitted to the bar. After the evacuation of New York he

established himself in that city, and from that time he dropped his first name.

He was regarded as "one of the most accomplished scholars, able

advocates, and fluent speakers of his time in the city, but violent in his

political feelings and conduct."

In June, 1802, he was made a puisne judge of the state supreme court, and in

1807 he succeeded William Patterson as associate justice of the United States

supreme court. Judge Livingston was appointed one of the trustees of the New

York society library, on its reorganization in 1788, and was elected 2d vice

president of the New York historical society on its organization in 1805. He was

also one of the first corporators of the public school system of New York city.

In 1818 the degree of LL. D. was conferred upon him by Harvard, and in 1790 he

delivered an oration before the president and other notable persons in St.

Paul's chapel, New York, on the occasion of the anniversary of the Declaration

of Independence. He also contributed political articles to the press of his

time under the pen-name of Decius.

--The second Philip's grandson, Walter

Livingston, lawyer, born in 1740; died in New York city, 14 May,

1797, was a resident of Albany, and a member of the provincial congresses that

were held in New York during April and May, 1775. In 1777 he was appointed one

of the judges for Albany by the convention that made his kinsman, Robert R.

Livingston, chancellor. He was a member of congress in 1784-'5, and appointed in

1785 one of the first commissioners of the treasury. Mr. Livingston married

Cornelia Schuyler, step-daughter of Dr. John Cochrane. In 1779 Mrs. Livingston

and Mrs. Cochrane were specially invited to dine General Washington,

whose headquarters were then at West Point. In the letter of invitation Washington

writes:

"If the ladies can put up with such entertainment, and will submit

to partake of it on plates once tin, but now iron (not become so by the labor

of scouring), I shall be happy to see them."

--Walter's son, Henry Walter Livingston, lawyer, born in Livingston Manor,

Linlithgow, New York, in 1768; died there, 22 December, 1810, was graduated at

Yale in 1786, and, after studying law, began the practice of his profession in

New York city. In 1792 he accompanied Gouverneur

Morris as private secretary, when the latter was sent as minister

plenipotentiary to France, and returned with him in 1794. Mr. Morris sent him to

the president with the statement, "You will find Mr. Livingston is to be

trusted, for, although at a tender age, his discretion may always be depended

on." For some time he was judge of the court of common pleas in

Columbia county, and was twice elected to congress, serving from 17 October,

1803, till 3 March, 1807. He married the granddaughter of the chief justice of

Pennsylvania, Mary Penn Allen, who was well known in New York society as

"Lady Mary."

John William Livingston, a

descendant of John Livingston, third son of the first Philip, naval officer,

born in New York city, 22 May, 1804; died there, 10 September, 1885, was the son

of William Turk, a surgeon in the United States navy, who married Eliza

Livingston. The son sought, in 1843, and obtained permission from the

legislature to assume his mother's surname. In March, 1824, he was appointed

midshipman in the United States navy from New York, and served in the

Mediterranean squadron during the war with the pirates. He received his

commission as lieutenant in June, 1832, and was assigned to the frigate "Congress,"

serving in the Pacific squadron in 1846-'7, seeing active service during the war

with Mexico, then in the East India squadron in 1848-'9, after which he was on

duty at the navy yard in New York.

In May, 1855, he was made commander, given charge of the "St.

Louis," and cruised off the coast of Africa in 1856-'8. He then

commanded the "Penguin," and was attached to the blockading

squadron in 1861, during which year he was promoted captain, and also captured

several vessels. In July, 1862, he was made commodore, and given charge of the

Norfolk navy yard after its evacuation by the Confederate forces until 1864, and

in 1865 he was sent to the naval station at Mound City, Illinois He was detached

from this duty in 1866, and ordered on special service, having charge

principally of the sale of condemned government vessels. In May, 1868, he was

commissioned rear-admiral, and in 1874 placed on the retired list, after which

he lived in New York city.

Robert R Livingston (the initial

g was assumed in order to distinguish him from other members of the family

having the same name), son of Robert Livingston, the second son of the first

Robert Livingston, jurist, born in New York in August, 1718; died in Clermont.

New York. 9 December, 1775, turned his attention to law, and became well known

in that profession. In 1760 he was made judge of the admiralty court, and in

1763 a justice of the New York supreme court. He represented Dutchess county in

the provincial assembly in 1759-'68, and was chairman of the committee that

corresponded with Robert Charles, the agent of New York in England. Judge

Livingston was a member of the stamp-act congress in 1765, and was energetic in

his refusal to sustain measures compelling the adoption of stamps. In 1767, and

again in 1773, he served on commissions to locate the boundary line between New

York and Massachusetts, and he was also a member of the committee of one hundred

that was elected in 1775 to control in all general affairs. He married Margaret,

daughter of Colonel Henry Beckman, and while he resided principally at Vermont,

he also had a city residence on Broadway, near Bowling Green. Sir Henry Moore,

governor of New York, describes him as "a man of great ability and many

accomplishments, and the greatest [richest] landholder, without any exception,

in New York." His daughter, Janet, married General Richard Montgomery.

See "History of Clermont or Livingston Manor," by Thomas S. Clarkson

(Clermont, 1869).

Robert R Livingston, son of

Robert R Livingston, statesman, born in New York city, 27 November, 1746; died

in Clermont, New York, 26 February, 1813, was graduated at Kings (now Columbia)

college in 1765, and studied law with William Smith and his kinsman, William

Livingston. He was admitted to the bar in 1773, and for a short time was

associated in partnership with John Jay, who had been

his contemporary in college. Mr. Livingston met with great success in the

practice of his profession, and was appointed recorder of the city of New York

by Governor William Tryon in 1773, but lost this office in 1775, owing to his

active sympathy with the revolutionary spirit of the times.

In 1775 he was elected to the provincial assembly of New York from Dutchess

county, and sent by this body as a delegate to the Continental congress, where

he was chosen one of a committee of five to draft the Declaration

of Independence. He was prevented from signing' this document by his hasty

return to the meeting of the provincial convention, taking his seat, in that

assembly on 8 July, 1776, the day on which the title of the "province"

was changed to that of the "state" of New York, and he was

appointed on the committee to draw up a state constitution. At the Kingston

convention in 1777 the constitution was accepted, and he was appointed first

chancellor of New York under its provisions, which office he held until

1801.

Chancellor Livingston continued a delegate to the Continental congress until

1777, was again one of its members in 1779-'81, and throughout the entire

Revolution was most active in behalf of the cause of independence. As chancellor

he administered the oath of office to George

Washington on his inauguration as first president of the United States. The

ceremony took place at the City Hall where the present S. S. sub-treasury

building stands, then fronting on Wall street. It had been specially fitted up

for the reception of congress, and the exact spot where Washington stood is now

marked by a colossal statue of the first president, which rests on the original

stone upon which the ceremony took place. The statue was designed by John Q. A.

Ward, and unveiled on the centennial celebration of the evacuation of New York,

25 November, 1883. Immediately after administering the oath Chancellor

Livingston exclaimed in deep and impressive tones: "Long live George

Washington, president of the United States."

He held office of secretary of foreign affairs for the United States in

1781-'3, and in 1788 was chairman of the New York convention to consider the

United States constitution, whose adoption he was largely instrumental in

procuring. The post of minister to France was declined by him in 1794, and he

also refused the secretaryship of the navy under Thomas

Jefferson, but in 1801, being obliged by constitutional provision to resign

the chancellorship, he accepted the mission to France. He enjoyed the personal

friendship of Napoleon Bonaparte, who, on

Livingston's departure in 1805, presented him with a splendid snuff-box

containing a miniature likeness of himself, painted by Isabey. It is said that "he

appeared to be the favorite foreign envoy."

He was successful in accomplishing the cession

of Louisiana to the United States in 1803, and also began the negotiations

tending toward a settlement for French spoliations on the commerce of the United

States. Subsequent to his resignation he traveled extensively through Europe.

While in Paris he met Robert Fulton, and together

they successfully developed a plan of steam navigation. Mr. Livingston had

previously been impressed with the advantage that was to be derived from the

application of steam to navigation, and he obtained from the legislature of the

state of New York the exclusive right to navigate its water-ways by steam power

for twenty years. He then constructed a boat of thirty tons burden, with which

he succeeded in making three miles an hour, but the concession was made on

condition of attaining a speed of four miles an hour, and other duties

intervened to prevent success. He made numerous experiments with Fulton,

and finally launched a boat on the Seine, which, however, did not fully realize

their expectations. Later, on their return to the United States, their

experiments were continued until 1807, when the "Clermont"

succeeded in accomplishing five miles an hour.

After his retire-meat from public service, Livingston devoted considerable

time and attention to the subject of agriculture, and it was through his efforts

that the use of gypsum for fertilizing purposes became general he was also the

first to introduce the merino sheep into the farming communities west of Hudson

river. He was the principal founder of the American academy of fine arts in New

York in 1801, and its first president, for some time president of the New York

society for the promotion of useful arts, and a trustee of the New York society

library on its reorganization in 1788. In 1792 the degree of LL.D. was conferred

upon him by the regents of the University of the state of New York. He published

an oration that he delivered before the Society of the Cincinnati on 4 July,

1787, an address to the Society for promoting the arts (1808), and "Essays

on Agriculture" and "Essay on Sheep" (New York, 1809,

and London, 1811). Benjamin Franklin called

him the "Cicero of America," and his statue, with that of George

Clinton, forms the group of the two most eminent citizens of New York being

placed by act of congress in the Capitol in Washington. See "

Biographical Sketch of Robert R. Livingston" by Frederic De Peyster

(New York, 1876).

Another son of the first Robert R Livingston, Henry

Beckman Livingston, soldier, born in Clermont, New York, 9 November,

1750; died in Rhinebeek, New York, 5 November, 1831, raised a company of

soldiers in August, 1775, and accompanied his brother-in-law, General Richard

Montgomery, on his expedition to Canada. For his service in the capture of

Chambly in 1775 he was voted a sword of honor by congress in December of that

year. In February, 1776, he became aide-de-camp to General

Philip Schuyler, and in November he was made colonel of the 4th battalion of

New York volunteers, but he resigned that command in 1779. He also served with Lafayette

in Rhode Island, and was with him at Valley Forge. At the close of the war

he was made a brigadier-general. While on his way to Albany in 1824, after

spending the night at Clermont, Lafayette

inquired of Colonel Nicholas Fish, "Where is my friend, Colonel Harry

Livingston?" Soon afterward, while the steamer was at the Kingston

dock, Colonel Livingston, having crossed the river in a small boat from

Rhinebeck, came on board. As soon as their eyes met, the two friends--the

marquis and the colonel--now old men, rushing into each other's arms, embraced

and kissed each other, to the astonishment of the Americans present. Colonel

Livingston was one of the original members of the New York society of the

Cincinnati. He inherited the Beckman estate at Rhinebeck, and married Miss Ann

Horne Ship-pen, niece of Henry Lee, president of the 1st congress.-

Edward Livingston, youngest son

of the first Robert R Livingston, statesman, born in Clermont, New York, 26 May,

1764; died in Rhinebeck, New York, 23 May, 1836, was graduated at Princeton in

1781, having entered the junior class, and then began the study of law in Albany

with John Lansing. He was admitted to practice in January, 1785, after studying

in New York city with his brother Robert, and at once took a high rank at the

New York bar, having for competitors Egbert Benson, Aaron

Burr, and Alexander Hamilton. He was

sent to congress in 1794, and twice re-elected, serving from 7 December, 1795,

till March, 1801. He opposed the administration, and introduced the resolution

calling for the instructions that had been given by the executive to John

Jay at the time of the formation of the treaty with Great Britain. With the

unanimous approval of his cabinet, Washington

declined to furnish these, although Livingston's resolution was carried by a

vote of 62 to 37. With Madison and Gallatin he

shared the distinction of being "the most enlightened members of

congress in the party of the opposition."

At the time of Jefferson's elevation to

the presidency a he vote existed in the electoral college, in consequence of

which the election passed to the house, where after 35 ballots he was chosen to

office. The New York delegation stood 6 to 4 in favor of Jefferson

and effort was made to induce Livingston to vote for Aaron

Burr, but without success. In March, 1801, he was appointed United States

attorney for the district of New York, and in August of the same year he was

elected mayor of New York city. During his mayoralty the present city hall was

built, the front and sides being constructed of white marble, while a

dark-colored stone was considered good enough for the north wall since "it

would be out of sight to all the world."

The yellow fever visited the city during the summer of 1803, and his

intrepidity in remaining at his post nearly cost him his life. Toward the close

of the epidemic he was stricken with the disease, and when his physician

recommended madeira for his recovery, not a bottle of that or any other kind of

wine was to be found in his cellar; he had prescribed every drop for others; but

as soon as this fact was known the best wines were sent to him from all

directions. A crowd thronged the street near his residence, No. 1 Broadway, to

obtain the latest news of his condition, and young people vied with each other

for the privilege of watching by his bed. His private affairs became involved,

so that he was unable to meet his obligations, and he was a debtor for a

considerable sum to the United States government. This condition of affairs was

due to a misappropriation of funds by his business agent. Without waiting for an

adjustment of his accounts, he voluntarily confessed judgment in favor of the

United States for $100,000, but the exact stun was afterward found to be

$43,666.21. He also conveyed all of his property to a trustee for sale, with

directions to apply all proceeds to the payment of his debts, and immediately

resigned from both his offices, although he continued to hold the mayoralty

until about October, 1803.

His elder brother, Robert Livingston, had just successfully completed the

negotiations by which the territory of

Louisiana became the property of the United States. In December, 1803, he

left New York for New Orleans by sailing vessel, reaching the latter city in

February, 1804, where he at once resumed his professional career, hoping thereby

to retrieve his fortunes. By accepting fees in land in lieu of ready money, he

soon acquired property that promised to become a fortune within a few years. He

found that the legal practice in the new province consisted of an unfortunate

medley of the civil and Spanish law, and in consequence he drew up a code of

procedure that in 1805 was adopted by the Louisiana legislature. Among his

private debts at the time of his leaving New York was a judgment that had been

assigned to Aaron Burr, for which the latter applied

through his agent in New Orleans. General James Wilkinson, obtaining this

information, attempted in court to connect Livingston with Burr's conspiracy;

but the effort failed, and Wilkinson made himself ridiculous by his interference

in the matter. One of the most celebrated eases of the time was his controversy

with Thomas Jefferson, who was then president

of the United States, over the title and possession of the property known as

Batture Sainte Marie.

Among his early clients was John Gravier, for whom he obtained a title to

that ground from the city of New Orleans, receiving as his fee part of the land.

When he was about to improve it, the people of New Orleans objected, claiming it

as their property, and appealed to the national government to sustain their

rights, in consequence of which the attorney-general decided in their favor, and

Livingston was dispossessed by the authority of the United States. An action was

at once brought by Livingston in the Federal court of New Orleans to recover

damages for his expulsion, and a restoration to possession, and somewhat later

another action was brought against Jefferson.

As the litigation approached decision in New Orleans, Jefferson

circulated a pamphlet that reflected somewhat sharply on his adversary, which

was promptly responded to in a similar way by Livingston. The latter finally

triumphed in the courts, although the delay was such that complete pecuniary

fruits of the victory only came to his family long after his death. The

unfortunate termination of his career in New York, and the accusation of

Wilkinson, destroyed Jefferson's confidence

in him, and so made his opposition possible in the Batture controversy. Later in

life the two men became reconciled, and cordial expressions of sympathy and

appreciation were received by Livingston from Monticello.

During the second war with England, Livingston acted as aide to Andrew

Jackson while the latter commanded the United States army in the southwest,

and he is said to have served as "aide-de-camp, military secretary,

interpreter, orator, spokesman, and confidential adviser upon all

subjects." His acquaintance with Jackson,

begun when they were fellow members of congress, now ripened into a deep

friendship that continued through life, and, before leaving New Orleans, Jackson

caused his portrait to be painted on ivory, and presented it to Livingston "as

a mark of the sense I entertain of his public services, and a token of my

private friendship and esteem."

In 1820 he was elected to the lower house of the Louisiana legislature, and

in 1822 he was sent to congress from the New Orleans district, serving, with two

re-elections, from 23 December, 1822, till 3 March, 1829. In 1823 he was

appointed, with Louis Moreau Lislet, to revise the civil code of Louisiana, a

work which was completed the next year, and substantially ratified by enactment.

Meanwhile, in 1821, he was intrusted solely with the task of preparing a code of

criminal law and procedure. The next year he made a report of his plan for the

work, which was afterward reprinted in London and Paris. His code was submitted

to the legislature in 1826, but never directly accepted. It was very favorably

received by the legal profession in this country and Europe, adding greatly to

his fame. It visibly influenced the legislation of several countries, and parts

of it were adopted entirely in Guatemala. He paid his long-standing debt to the

government in 1826, with interest amounting to $100,014.89, by the disposal to

the United States of property in New Orleans, to which his title was clear and

undisputed.

The action of President Jackson in directing

the United States treasurer to receipt for this sum caused some unfortunate

comment at the time, especially as others that were indebted to the government

were confined in prison. As soon as this receipt was recorded, Livingston at

once presented an account for salary that was due him as member of congress,

which, on account of his being a debtor to the government, he had previously

been unable to collect. During his career in congress his course was marked by a

close adherence to the routine business of legislation, and by his efforts to

reform the criminal code, to extend laws for the protection and relief of

American seamen in foreign lands, and to promote the establishment and increase

of the navy. In 1829 he was chosen United States senator from Louisiana, but

served only until March, 1831, when he was invited to accept the office of

secretary of state, which had been made vacant by the resignation of Martin

Van Buren.

He was generally credited with the preparation of the state papers of Jackson,

and the celebrated nullification proclamation of 10 December, 1832, is supposed

to have been written by him. He was sent as minister to France in 1833, and

resided in Paris until 1835, conducting with great skill the difficult matters

that resulted in the payment of the French spoliation claims. His friendship

with Lafayette, beginning when as a boy he

visited the marquis at his headquarters, and continuing through long years by

correspondence, and kind attentions to Livingston's son, Lewis, was now renewed.

On his return home, Livingston retired to the Montgomery place near

Rhinebeck, which had been bequeathed to him in 1828 by his sister Janet, the

wife of General Richard Montgomery. In January, 1836, he appeared before the

supreme court in Washington as counsel for the city of New Orleans against the

United States, and this was his last absence from his family. Livingston's

celebrity as a lawyer was due to his extended knowledge of law, having probably

no superior as a master of the various systems in the civilized world. His works

include "Judicial Opinions delivered in the Mayor's Court of the City of

New York in the Year 1802" (New York, 1803); "Report of the Plan of

the Penal Code" (New Orleans, 1822); "System of Penal Law for the

State of Louisiana" (1826); "System of Penal Law for the United

States" (Washington, 1828); also "Complete Works on Criminal

Jurisprudence" (New York, 1873). See "Recollections of

Livingston," by Auguste D'Avezac, originally published in the

"Democratic Review" (1840), and "Life of Edward Livingston,"

by Charles H. Hunt (New York, 1864).

Mr. Livingston married in 1805, as his second wife, Louise D'Avezac, widow of

a Jamaica planter named Moreau. She was barely nineteen years of age at the time

of her second marriage, and unable to speak English; but she soon acquired the

language, and rendered great aid to her husband by her tact and grace. Mrs.

Livingston was an ardent patriot, and never allowed an affront to the United

States or a word in its disparagement to pass unrebuked. One day the Prussian

ambassador at Paris spoke of the city of Washington as a mere village, and,

turning to her, asked what its population was. She replied, with a smile. "A

peu pres celle de Potsdam." See "Memoir of Mrs. Edward

Livingston," by Louise Livingston Hunt (New York, 1886).

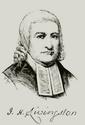

John Henry Livingston, grandson

of Gilbert Livingston, third son of the first Robert Livingston, clergyman, born

in Poughkeepsie, New York, 30 May, 1746; died in New Brunswick, New Jersey, 20

January, 1825, was graduated at Yale in 1762, and began the study of law, but

impaired health led to its discontinuance. On his recovery he determined to

prepare for the ministry, and accordingly went to Holland, where he entered the

University of Utrecht. In 1767 he received his doctorate from the university, on

examination, and was ordained by the classis of Amsterdam, after being invited

to become one of the pastors of the Reformed Dutch church in New York. While in

Holland he procured the independence of the American churches from the Dutch

classis, and within two years from the time of his return had succeeded in

reconciling the Coetus and Conferentic parties, into which the church had

divided. He reached New York in September, 1770, and at once entered on the

active duties of his pastorate, having the North Dutch church at the corner of

Fulton and William streets under his charge. He continued in this office until

1810, although subsequent to 1775, owing to the British occupation of New York,

he spent some time at the Livingston Manor, also preaching at Kingston, New

York, in 1776, at Albany in 1776-'9, at Lithgow in 1779-'81, and at

Poughkeepsie, New York, in 1781-'3. After the evacuation of New York in 1783 he

returned to his pastorate, being the only survivor of his four colleagues, and

for three years he alone performed the work which formerly required the services

of these ministers.

In October, 1784, he received the appointment of professor of theology from

the general synod on the recommendation of the theological faculty of Utrecht,

but it was not until 1795 that a regular seminary was opened in Flatbush, L. I.

This was closed two years later for lack of proper support. He then returned to

New York, and in 1807 was made professor of theology and president of Queen's

college (now Rutgers), New Brunswick, New Jersey In 1810 he removed to that

place, where he continued to hold these two offices until his death. Mr.

Livingston was an ardent patriot, and during the sessions of the Provincial

congress that were held in New York in 1775 he was frequently called on to open

the meetings with prayer. He was vice president of the first missionary society

in New York, having for its object the propagation of the gospel among the

American Indians, and he was also one of the regents of the University of the

state of New York in 1784-'7.

His publications include, besides several sermons and addresses,

"Funeral Service, or Meditations adapted to Funeral Addresses" (New

York, 1812), and "A Dissertation on the Marriage of a Man with his

Sister-in-Law" (1816); and in 1787 he was chairman of a committee to make

selection of psalms for the use of the church in public worship. He was styled

"the father of the Dutch Reformed church in this country." See

"Memoirs of John H. Livingston," by Alexander Gunn (New York, 1829).

James Livingston, soldier, born

in Canada 27 March, 1747; died in Saratoga county, N. g., 29 November, 1832, was

the son of John, and grandson of Robert, the nephew of the first Robert. His

father married Catherine, daughter of General Abraham Ten Broeck, and settled in

Montreal. At the beginning of the Revolutionary war James was given command of a

regiment of Canadian auxiliaries which he had raised. This regiment was attached

to the command of General Richard Montgomery,

and participated in the capture of Fort Chambly with its garrison and stores.

Later he accompanied General Montgomery on

his invasion of Canada, and participated in the assault on Quebec, where the

commanding general was killed.

Subsequently he continued with the American army until the close of the war,

and his presence is noted at the battle of Stillwater, in 1777, and at the

surrender of Burgoyne in October of that year.

Colonel Livingston had command of Stony Point at the time of Benedict

Arnold's treason in 1780, and while as a subordinate of Arnold's

he was liable to suspicion, Washington

himself expressed to him his gratification "that the post was in the

hands of an officer so devoted as yourself to the cause of your country."

Lieutenant-Colonel Richard and Captain Abraham, of the same corps, were his

brothers. A very elaborate history of "The Livingstons of Callendar and

their Principal Cadets," by Edwin Brockholst Livingston, to be issued

in six parts, has been privately printed in Europe for presentation only, and

the edition is limited to seventy-five sets (1887).

Edited Appletons Encyclopedia, Copyright

© 2001 VirtualologyTM