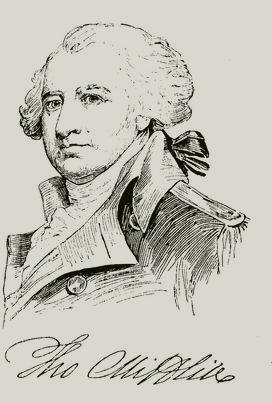

Thomas Mifflin, 5th President of the United States in Congress Assembled,

Signer US Constitution, Conway Cabal - A Stan Klos Biography

Thomas Mifflin

5th President of the United States

in Congress Assembled

November 3, 1783 to June 3, 1784

Click on an image to view full-sized

Click on an image to view full-sized

MIFFLIN, Thomas, soldier, born

in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1744; died in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, 20 ,

January, 1800. He was graduated at Philadelphia college in 1760, entered a

counting-house, traveled in Europe in 1765, and on his return engaged in

commercial business in partnership with a brother.

In 1772 and 1773 he was a representative in the legislature, and in 1774 was

one of the delegates sent to the Continental congress, and served on important

committees. When the news came of the fight at Lexington he eloquently advocated

resolute action in the town-meetings, and when troops were enlisted he was

active in organizing and drilling one of the first regiments, and was made its

major, thereby severing his connection with the Quaker society, in which he was

born and reared.

General Washington chose him as his first

aide-de-camp, with the rank of colonel, soon after the establishment of his

headquarters at Cambridge. While there he led a force against a British

detachment. In July, 1775, he was made quartermaster-general of the army, and,

after the evacuation of Boston by the enemy, was commissioned as

brigadier-general, 19 May, 1776. He was assigned to the command of a part of the

Pennsylvania troops when the army lay encamped before New York, and enjoyed the

particular confidence of the commander-in-chief. His brigade was described as

the best disciplined of any in the army. In the retreat from Long Island he

commanded the rear-guard, and through a blunder received the order to cover the

retreat before all of the troops had embarked, but, after marching his men to

the ferry, regained the lines before the enemy discovered that the post was

deserted. In compliance with a special resolve of congress, Mifflin resumed the

duties of quarter-master-general.

In November, 1776, he was sent. to Philadelphia to represent to

the Continental Congress the

critical condition of the army, and to excite the patriotism of the

Pennsylvanians. After listening to him, congress appealed to the militia of

Philadelphia and the nearest counties to join the army in New Jersey, sent to

all parts of the country for re-enforcements and supplies, and ordered Mifflin

to remain in Philadelphia for consultation and advice. He organized and trained

the three regiments of associators of the city and neighborhood, sending a body

of 1,500 to Trenton. In January, 1777, accompanied by a Committee of the

legislature, he made the tour of the principal towns of Pennsylvania, and by his

stirring oratory brought recruits to the ranks of the army. He came up with

re-enforcements before the Battle of Princeton was fought. In recognition of his

services, congress commissioned him as major-general on 19 February, and made

him a member of the board of war.

He shared the dissatisfaction at the "Fabian policy" of General

Washington, and sympathized with the views of General Horatio Gates

and General

Thomas Conway, but afterward declared that he had not shared in the desire to

elevate the former to the supreme command. The cares of his various offices so

impaired General Mifflin's health that he offered his resignation, but, congress

refused to accept it. When the friends of Washington overcame the Conway Cabal,

Mifflin was replaced by General Nathanael Greene

in the quartermaster's department in March, 1778, and in October he and Gates

were discharged from their places on the board of war.

An investigation of his conduct was ordered by congress in consequence of

charges that the distresses of the army at Valley Forge were due to the

mismanagement of the quartermaster-general. When the decree was revoked, after

he had himself demanded an examination, he resigned his commission, but congress

again refused to accept it, and placed in his hands $1,000,000 to settle

outstanding claims. In January, 1780, he was appointed on a board to devise

means for retrenching expenses. After the achievement of the

Treaty of Paris he was

elected as a delegate to the United States Unicameral Congress.

In a twist of fate, Thomas Mifflin was elected

President of the United States in Congress Assembled, 3 November, 1783 with the

Journals of the United States in Congress Assembled reporting:

Pursuant to the Articles of Confederation, the

following delegates attended:

FROM THE STATE OF NEW HAMPSHIRE, Mr. A[biel] Foster, MASSACHUSETTS, Mr.

E[lbridge] Gerry, who produced a certificate under the seal of the State, signed

John Avery, Mr. S[amuel] Osgood, RHODE ISLAND AND PROVIDENCE PLANTATIONS, Mr.

W[illiam] Ellery and Mr. D[avid] Howell, CONNECTICUT, Mr. S[amuel] Huntington

and Mr. B[enjamin] Huntington, NEW YORK, Mr. James Duane, NEW JERSEY, Mr. E[lias]

Boudinot, MARYLAND, Mr. D[aniel] Carroll,Mr. J[ames] McHenry, VIRGINIA.Mr. J[ohn]

F[rancis], Mr. A[rthur] Lee, NORTH CAROLINA, Mr. [Benjamin] Hawkins, and

Mr. [Hugh] Williamson, SOUTH CAROLINA, Mr. J[acob] Read, Mr. R[ichard]

Beresford, Seven states being represented, they proceeded to the choice of a

President; and, the ballots being taken, the honorable

Thomas Mifflin was elected.

One of the most remarkable events of the United

States history occurred under Mifflin's Presidency the very next month. In

November of 1783 the British finally evacuated New York and Congress made the

momentous decision to place the Continental Army on a "Peace Footing ".

It was in Annapolis, where the US Government convened that the last great act of

the Revolutionary War occurred in 1783. George

Washington was formally received by President Thomas Mifflin and Congress.

Instead of declaring himself King, resigned his commission as Commander-in-Chief

to the President of the United States.

What made this action especially remarkable was

that George Washington, at his pinnacle of his power and popularity, surrendered

the commission to President

Thomas Mifflin. It was Mifflin who, as a Major General and a member of the

Board of War, conspired to replace Washington as Commander-in-Chief with Horatio

Gates in 1777. What follows is The United States in Congress Assembled Journal

account of

George Washington's December 23, 1783 resignation:

According to order,

his Excellency the Commander in Chief was admitted to a public audience, and

being seated, and silence ordered, the President, after a pause, informed him,

that the United States in Congress assembled, were prepared to receive his

communications; Whereupon, he arose and addressed Congress as follows:

'Mr. President:

The great events on which my resignation depended, having at length taken place,

I have now the honor of offering my sincere congratulations to Congress, and of

presenting myself before them, to surrender into their hands the trust committed

to me, and to claim the indulgence of retiring from the service of my country.

Happy in the

confirmation of our independence and sovereignty, and pleased with the

opportunity afforded the United States, of becoming a respectable nation, I

resign with satisfaction the appointment I accepted with diffidence; a

diffidence in my abilities to accomplish so arduous a task; which however was

superseded by a confidence in the rectitude of our cause, the support of the

supreme power of the Union, and the patronage of Heaven.

The successful

termination of the war has verified the most sanguine expectations; and my

gratitude for the interposition of Providence, and the assistance I have

received from my countrymen, increases with every review of the momentous

contest.

While I repeat my

obligations to the army in general, I should do injustice to my own feelings not

to acknowledge, in this place, the peculiar services and distinguished merits of

the gentlemen who have been attached to my person during the war. It was

impossible the choice of confidential officers to compose my family should have

been more fortunate. Permit me, sir, to recommend in particular, those who have

continued in the service to the present moment, as worthy of the favorable

notice and patronage of Congress.

I consider it an

indispensable duty to close this last act of my official life by commending the

interests of our dearest country to the protection of Almighty God, and those

who have the superintendence of them to his holy keeping. Having now finished

the work assigned me, I retire from the great theatre of action, and bidding an

affectionate farewell to this august body, under whose orders I have so long

acted, I here offer my commission, and take my leave of all the employments of

public life'

George Washington then

advanced and delivered to President Mifflin his

commission, with a copy of his address, and returned to having resumed

his place, whereupon the President

Thomas Mifflin returned him the following answer:

Sir,

The United States in

Congress assembled receive with emotions, too affecting for utterance, the

solemn deposit resignation of the authorities under which you have led their

troops with safety and triumph success through a long a perilous and a doubtful

war. When called upon by your country to defend its invaded rights, you accepted

the sacred charge, before they it had formed alliances, and whilst they were it

was without funds or a government to support you. You have conducted the great

military contest with wisdom and fortitude, through invariably regarding the

fights of the civil government power through all disasters and changes. You

have, by the love and confidence of your fellow-citizens, enabled them to

display their martial genius, and transmit their fame to posterity. You have

persevered, till these United States, aided by a magnanimous king and nation,

have been enabled, under a just Providence, to close the war in freedom, safety

and independence; on which happy event we sincerely join you in congratulations.

Having planted

defended the standard of liberty in this new world: having taught an useful

lesson a lesson useful to those who inflict and to those who feel oppression,

you retire from the great theatre of action, loaded with the blessings of your

fellow-citizens, but your fame the glory of your virtues will not terminate with

your official life the glory of your many virtues will military command, it will

continue to animate remotest posterity ages and this last act will not be among

the least conspicuous

We feel with

you our obligations to the army in general; and will particularly charge

ourselves with the interests of those confidential officers, who have attended

your person to this interesting affecting moment.

We join you in

commending the interests of our dearest country to the protection of Almighty

God, beseeching him to dispose the hearts and minds of its citizens, to improve

the opportunity afforded them, of becoming a happy and respectable nation. And

for you we address to him our earnest prayers, that a life so beloved may be

fostered with all his care; that your days may be happy, as they have been

illustrious; and that he will finally give you that reward which this world

cannot give.

President Thomas Mifflin's third month in office

was equally eventful as he presided over another great US event. On January 14,

1784 Congress finally assembled enough States to ratify the

Definitive Treaty of Peace , which half-ended the War with Great

Britain (King

George III did not ratify the treaty for Britain until April 9, 1784 which

officially ending the War). On January 21st the following proclamation was

published and appeared in the Pennsylvania Gazette:

PHILADELPHIA, January 21.

By the UNITED STATES in CONGRESS assembled.

A PROCLAMATION.

WHEREAS Definitive

Articles of peace and friendship, between the United States of America and his

Britannic Majesty, were concluded and signed at Paris on the 3d day of

September, 1783, by the Plenipotentiaries of the said United States and of His

said Britannic Majesty, duly and respectively authorized for that purpose, which

definitive articles are in the words following:

And we, the United

States in Congress assembled, having seen and duly considered the definitive

articles aforesaid, did, by a certain article, under the seal of the United

States, bearing date this 14th day of January, 1784, approve, ratify and confirm

the same, and every part and clause thereof, engaging and promising that we

would sincerely and faithfully perform and observe the same, and never to suffer

them to be violated by any one, or transgressed in any manner, as far as should

be in our power.

And being sincerely

disposed to carry the said articles into execution, truly, honestly and with

good faith, according to the intent and meaning thereof, We have thought proper,

by these presents, to notify the premises to all the good citizens of these

States, hereby enjoining all bodies of magistracy, legislative, executive and

judiciary, all persons bearing office, civil or military, of whatever rank,

degree or powers, and all others, the good citizens of these states, of every

vocation and condition, that, reverencing those stipulations entered into on

their behalf, under the authority of that federal bond, by which their existence

as an independent people is bound up together, and is known and acknowledged by

the nations of the world, and with that good faith, which is every man's surest

guide, within their several offices, jurisdictions and vocations, they carry

into effect the said definitive articles, and every clause and sentence thereof,

strictly and completely.

Given under the seal of the United States. Witness his

Excellency THOMAS MIFFLIN, our President, at Annapolis, this 14th day of

January 1784, and of the sovereignty and independence of the United

States of America, the eighth.

In March 1784 a congressional committee led by

Thomas Jefferson proposed to divide up sprawling western territories into

states, to be considered equal with the original 13.

Whereas the general Assembly of Virginia at

their session, commencing on the 20 day of October, 1783, passed an act to

authorize their delegates in Congress to convey to the United States in

Congress assembled all the right of that Commonwealth,

to the territory northwestward of the river Ohio: And whereas the delegates of

the said Commonwealth, have presented to Congress the form of a deed proposed

to be executed pursuant to the said Act, in the words following:

To all who shall see these presents, we

Thomas Jefferson, Samuel Hardy, Arthur Lee and James Monroe, the underwritten

delegates for the Commonwealth of Virginia, in the Congress of the United

States of America, send greeting:

Known as the Ordinance of 1784, Jefferson's

committee not only proposed a ban on slavery in these new states but everywhere

in the U.S. after 1800. This proposal is narrowly defeated by the Southern

Contingent of Congress despite President Thomas Mifflin's support. The

chance of abolishing slavery nationally is lost until the Civil War. It wouldn't

be until July 1787, under President Arthur St. Clair,

that an Ordinance would be passed to govern free of slavery the

Northwest Territory which later became the

states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan and Wisconsin.

Earlier in 1784 Mifflin's Congress, through the

efforts of James Monroe, granted the necessary ships papers to the Empress

of China:

We the United States in Congress assembled,

make known, that John Green, captain of the ship called the Empress of China,

is a citizen of the United States of America, and that the ship which he

commands belongs to citizens of the said United States, and as we wish to see

the said John Green prosper in his lawful affairs, our prayer is to all the

beforementioned, and to each of them separately, where the said John Green

shall arrive with his vessel and cargo, that they may please to receive him

with goodness, and treat him in a becoming manner, permitting him upon the

usual tolls and expences in passing and repassing, to pass, navigate and

frequent the ports, passes and territories, to the end, to transact his

business where and in what manner he shall judge proper, whereof we shall be

willingly indebted.

On August 30, 1784 The Empress

of China reached Canton, China. It would return to New York City months later

filled with a cargo of spices, silks, exotic plants, new metal alloys and tea

inspiring a host of US Merchants to enter into the Far East trade.

Mifflin chose not to serve his

full one year term as President of the United States in Congress Assembled and

resigned on June 3, 1784. The following motion was entered in to the

Journals of the United States in Congress Assembled on June 3, 1784:

Resolved, That the thanks

of Congress be given to his Excellency Thomas Mifflin, for his able and

faithful discharge of the duties of President, whilst acting in that important

station

Thomas Mifflin interest in politics did not end

with the Presidency. He was a member of the Pennsylvania Legislature and was elected speaker

in 1785. In 1787

Mifflin was elected as a delegate to the convention that framed the constitution of the United

States. Mifflin attended regularly, but made no speeches and did not play a

substantial role in the Convention. He was one of its signers of the US

Constitution on September 17, 1787.

He was elected a member of the supreme

executive council of Pennsylvania in 1788, succeeded to its presidency, and

filled that office till 1790. He presided over the convention that was called to

devise a new constitution for Pennsylvania in that year, was elected the first

governor over Arthur St. Clair, and re-elected

for the two succeeding terms of three years. He raised Pennsylvania's quota of

troops for the suppression of the whiskey insurrection, and served during the

campaign under the orders of Governor Henry Lee, of Virginia. Governor Mifflin was a member of the American philosophical society from

1768 till his death.

Not being eligible under the constitution for a fourth term in the governor's

chair, he was elected in 1799 to the assembly during which time he affiliated

himself with the emerging Republican Party. Thomas Mifflin, like his colleague

Thomas Jefferson was wealthy most of his life, but a copious spender. Demands

from his creditors forced him to leave Philadelphia in 1799, and he died in

Lancaster the following year at 56. Pennsylvania remunerated his burial expenses

at the local Trinity Lutheran Church.

Thomas's cousin, Warner Mifflin, reformer, born in Accomae county,

Virginia, 21 October, 1745 ; died near Camden, Delaware. 16 October, 1798, was

the son of Daniel Mifflin, a planter and slave-owner, and the only Quaker within

sixty miles of his plantation. The son early cherished an interest in behalf of

the slaves. In giving an account of his conversion to anti-slavery views, he

writes of himself: "About the fourteenth year of my age a circumstance

occurred that tended to open the way for the reception of those impressions

which have since been sealed with indelible clearness on my understanding. Being

in the field with my father's slaves, a young man among them questioned me

whether I thought it could be right that they should be toiling in order to

raise me, and that I might be sent to school, and by and by their children must

do so for mine. Some little irritation at first took place in my feelings, but

his reasoning so impressed me as never to be erased from my mind. Before I

arrived at the age of manhood I determined never to be a

slave-owner."

Nevertheless, he did become the owner of slaves-some on his marriage through

his wife's inheritance, and others from among his father's, who followed him to

his plantation in Delaware, whither the son had removed and settled. Finally,

determining that he would "be excluded from happiness if he continued in

this breach of the divine law," he freed all his slaves in 1774 and

1775, and his father followed the example. The son, on the day fixed for the

emancipation of his slaves, called them one after another into his room and

informed them of his purpose to give them their freedom, and this is the

conversation that passed with one of them : "Well, my friend

James," said he, "how old art thou? I am twenty-nine and a half

years, master." "Thou should'st have been free, as thy white brethren

are, at twenty-one. Religion and humanity enjoin me this day to give thee thy

liberty; and justice requires me to pay thee for eight years and a half service,

at the rate of ninety-one pounds, twelve shillings, and sixpence, owing to thee;

but thou art young; and healthy; thou had'st better work for thy living; my

intention is to give thee a bond for it, bearing interest at seven and a half

percent. Thou hast now no master but God and the laws."

From this time until his death his efforts to bring about emancipation were

untiring. Through his labors most of the members of his society liberated their

slaves. He was an elder of the Society of Friends, and traveled from state to

state preaching his anti-slavery doctrines among his people, and in the course

of his life visited all the yearly meetings on the continent. He was much

encouraged in his work by the words of the preamble of the Declaration of

Independence. Referring to these, he writes : "Seeing this was the very

substance of the doctrine I had been concerned to promulgate for years, I became

animated with hope that if the representatives were men, and inculcated these

views among the people generally, a blessing to this nation would accompany

these endeavors."

In 1782 he appeared before the legislature of Virginia, and was instrumental

in having a law enacted that admitted of emancipation, to which law may be

attributed the liberation of several thousand Negroes. In 1783 he presented a

memorial to congress respecting the African slave-trade, and he subsequently

visited, in the furtherance of his work, the legislatures of Pennsylvania,

Maryland, and Delaware. In 1791 he presented his noted "Memorial to the

President, the Senate, and the House of Representatives of the United

States" on the subject of slavery, and, on account of some reflections

that were cast on him, he published a short time afterward his serious

expostulations with the house of representatives in relation to the principles

of liberty and the inconsistency and cruelty of the slave-trade and slavery.

These essays show the undaunted firmness and zeal of the writer, his cogent

reasoning and powerful appeals to the understanding and the heart.

From conviction he was against war, and on principle opposed the Revolution.

On the day of the battle of Germantown he was attending the yearly meeting of

the Quakers at Philadelphia, and the room in which they were assembled was

darkened by the smoke of the battle. At this meeting the Friends renewed their "testimony"

against the spirit of war, and chose Mifflin to undertake the service of

communicating it to General Washington and General Howe. To perform this duty,

he had to walk in blood and among the dead bodies of those that had fallen in

the fight. In his conversation with Washington he said : "I am opposed

to the Revolution and to all changes of government which occasion war and

bloodshed." After Washington was elected president, Mifflin visited him

in New York, and in the course of the interview the president, recollecting an

assertion of Mifflin's at Germantown, said: "Mr. Mifflin, will you

please tell me on what principle you were opposed to the Revolution?"

"Yes, Friend Washington, upon the principle that I should be opposed to a

change in the present government. All that was ever gained by revolution is not

an adequate compensation for the poor mangled soldiers, for the loss of life or

limb." To which Washington replied: "I honor your sentiments;

there is more in that than mankind have generally considered." With

reference to Mifflin, Brissot, in his "Examination of the Travels of

Chastellux in America," says: "I was sick, and Warner Mifflin

came to me. It is he that first freed all his slaves; it is he who, without a

passport, traversed the British army and spoke to General Howe with so much

firmness and dignity; it is he who, fearing not the effects of the general

hatred against the Quakers, went, at the risk of being treated as a spy, to

present himself to General Washington, to justify to him the conduct of the

Quakers; it is he that, amid the furies of war, equally a friend to the French,

the English, and the Americans, carried succor to those who were suffering.

Well! this angel of peace came to see me."